MRI Art

March 18, 2019

Science continues to be a field of infinite uncertainty as individuals interchange between research ventures and artistic visions to capture nature’s exuding radiance. Whether it be through the visualizations of magnetic imaging resonance pattern scans (MRI) scans or photography through the microscope, the fluidity between science and art is on the rise. Intrigued and enlightened, the public both learns and admires a different perspective of science through these interactive exhibits and immersive images. As a result, the unseen beauty of the natural world is able to serve as an inspiration for many.

Walking into a black room, dust gets scuffed up from the floor, filling the air with earthy tones. The humming of chaotic insects can be heard overhead and the rapidly flashing LED monitors strike the creatures’ blue-tinted backs.

Known for the sensational diversity in his work, French artist Pierre Huyghe continues to exceed the limitations of the art world, no matter what form his art takes. Whether it be an interactive soundtrack, sculpture or monitor, the unique facets of his artwork create an unparalleled experience for the viewer. Inside his rendered conscious visual exhibit in London, called “UUmwelt,” over 10,000 living bluebottle flies circle the expanse of the gallery, perching on bright screens and a cool floor in addition to their airborne journey. Accompanying the winged creatures are strategically sanded walls and fluctuating humidity.

Huyghe frequently incorporates dramatically different mediums to compose an ecosystem that connects humans, animals and technological influence in his exhibitions. The flies provide a sense of unpredictability and never-ending motion as the sanded walls release a plethora of dust waiting to be moved about the gallery. Concurrently, the number of people present alters the temperature and humidity, even if ever so slightly. Although seemingly indifferent, Huyghe strives to emphasize the interrelations between the biotic and the abiotic, and thus, has light, temperature and humidity sensors that are constantly analyzing the exhibit’s conditions and changing the rate of the flashing monitors accordingly.

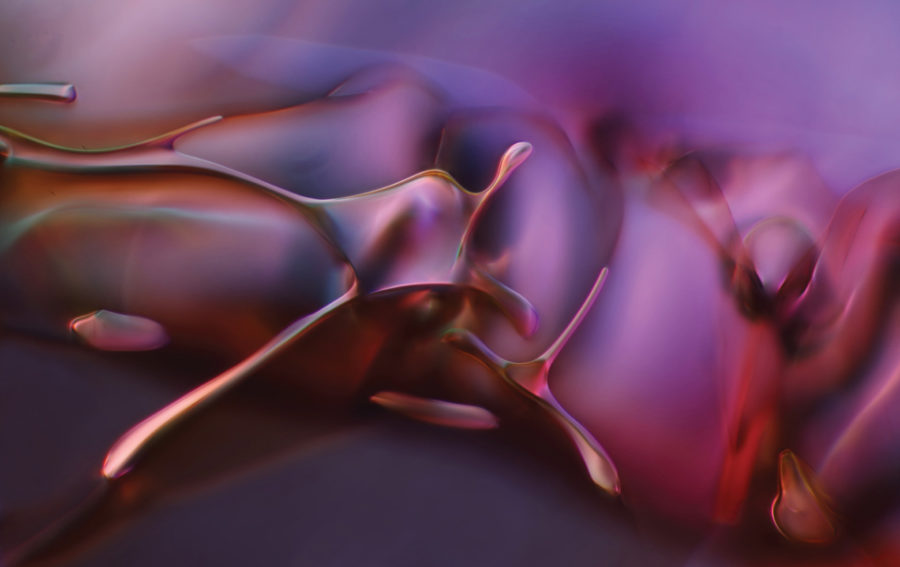

In order to regulate the speed at which each image produced by the MRI scan appears for, Huyghe embeds the collected light and humidity data through various algorithms. As a result, the embedded LED monitors can flicker the strange creations onto the screen surface up to a dozen times a second. Hence, insufficient time is left for the mind to analyze each individual frame, forcing the already oblique images to fade into nothing more but barely recognizable figures.

For a fleeting moment, the observer may be able to pick out a somewhat definite figure amongst the muddled explosion of color emitted by the monitors and projected onto the screen. Perhaps what you see is a brown beetle, while another spectator claims to have seen a brown bear. Alas, the chance to dwell upon one’s findings is ripped away as the image contorts into something unrecognizable, blending back into the dimensions of the frame once more.

Inevitably, countless moving parts and mechanics of the piece create room for discussion, as the perception of the work is entirely up to the viewer. When shown Huyghe’s unique exhibition, Alexander Nemerov, a Stanford art historian and professor, delves into a possible interpretation of the piece. “It creates a space wherein we can reflect, think, and in this case, on the increasing inability to think at all in the midst of whirring images that occur faster than we can comprehend them,” he said. “Accompanied by the restless disturbing buzz of flies and their implication of rot and death, the piece also suggests that we speed along, almost mindlessly, to the background hum of our own mortality.”

<

The piece almost suggests that we speed along almost mindlessly, to the background hum of our own mortality.

— Alexander Nemerov

The process of developing these perplexing images begins with medical professionals taking MRI’s of Huyghe’s participants while they are shown a collection of images or described ideas. The recorded neural activity is then sent to Huyghe’s collaborator, Japanese neuroscientist, Yukiyasu Kamitani, who developed an artificial intelligence software that is able to convert the collected data into existent images through a deep neural network. This equipment draws from a preexisting bank of images and attempts to reconstruct and reproduce the participant’s conscious.

Kamitani’s machine-based learning technology was originally used in attempts to decode brain activity as people slept. With the combination of MRI scans and verbal reports, the decoding models produce a relatively accurate detection and representation of the imagery.

This particular union of science and art is relatively new, Huyghe being a pioneer of the style. To blur the line that separates the two fields, commonly perceived by many as polar opposites, is revolutionary in the name of the exact definition of art. Palo Alto High School art teacher Kate McKenzie is one of many who is intrigued by the endless possibilities the future of science and art beholds. “There are still so many unknowns in science and in art and when you put the two together it creates a vast playground waiting to be explored,” she said.

The world of science and technology surges forward and with it, a plethora of closeted ideas to bring to life and an entire universe to explore. Huyghe is one of the first, but as technology is used more frequently as an intermediate between science and art, society’s natural ability to create and discover can only flourish.