Sleep Tight

What drives the sleeping mind to unconsciously fabricate vivid narratives that may reflect aspects of our lives? This remains one of humanity’s most intricate mysteries, revealed through compelling personal stories.

December 6, 2018

The brain’s inclination to dream is one of life’s most compelling and open-ended mysteries. Sleep is a necessary function of the human body, and as something that consumes up to a third of our lives, there is still much that is left for speculation. Why do we dream? What do these dreams mean? Where do these images originate within our minds? Many scientists have attempted to respond to these questions through theories regarding the enigma of dreaming and the basis of sleep. Despite the fact that most scientists are approaching the mystery from alternative angles, they often reach a similar conclusion: one of the most effective ways to understand the complex variations of disorders and unusual experiences linked to sleep is through the chilling, emotional, and powerful personal narratives of individuals.

His eyes shoot open from the brightness of his room. His grip tightens on his bedsheets as he gasps for air and is caught in a whirl of mind-numbing panic. The remaining dampness of tears stream down his face, sweat soaking into his mattress and clinging to his back. Suddenly, a face of concern appears above him, shouting his name over and over, snapping him out of the realm to which he had been transported. The face materializes—it’s his mother—and she grabs his shoulders, reassuring him that he is safe. The voice falls flat as his mind surfaces into the present, but he is still frozen with fear. A night like this is not uncommon for Paly graduate Oliver Miller, whose name has been changed for this story. Miller has had night terrors for years.

“My terrors usually tell me a lot about the stress I’m going through,” he explained. Miller struggled with heavy childhood trauma, and as a result, his physicians determined that his nightmares are the form that the loneliness he experienced as a teenager had taken over time. “I have found that loss and being alone has developed into my biggest fear.”

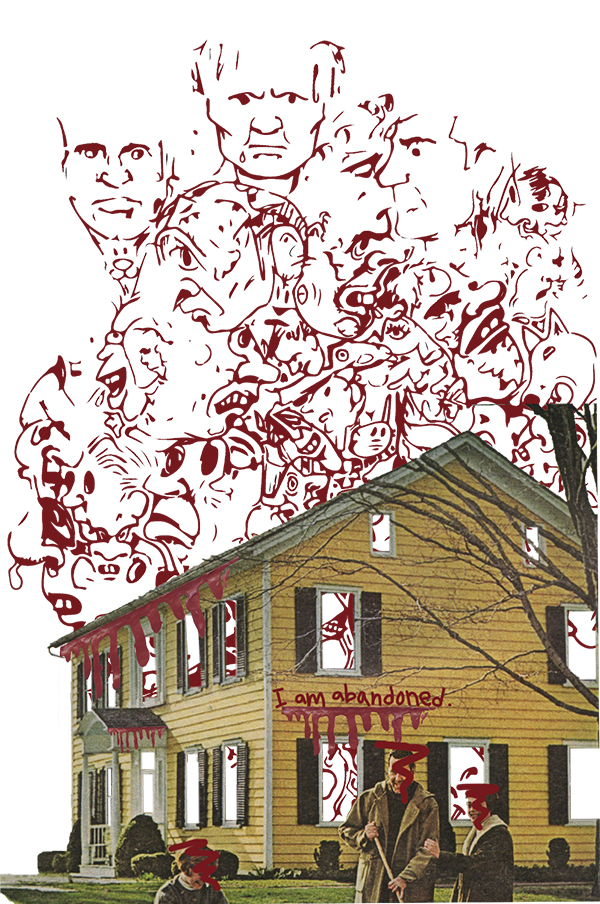

Miller has been haunted by a recurring dream that slips its way into his mind every so often. “I walk into a house with desolate surroundings with my immediate family. We all walk into a small room: bleak, dark, and bare. This room is huge, with vaulted ceilings, no furniture, and only dimly illuminated through one small window. Suddenly, the bedroom door slams behind me, and I immediately start to realize my family is fleeing from the house. I try to get out of the room but there is no longer a door; the room is completely sealed. I sprint to the window to see my family walking away. I punch through the window as hard as I can, kicking, and doing everything I can physically do to get out. I am abandoned.” The dream often ends abruptly as he curls onto the floor and the house sinks into the ground, leaving Miller in tears.

The sense of loneliness prevalent throughout his teenage years is represented in his dream through this apparent abandonment. This observation correlates directly with the work of Sigmund Freud, a widely-established neurologist. One of his many eminent contributions to the world of psychology is the development of his book, The Interpretation of Dreams, in which he introduces his theory that humans dream in order to satisfy their unconscious desires, thoughts and motivations. Freud believed that traumatic events experienced in one’s childhood had immense long term effects, later presented in our adult lives. According to Freud’s theories, one’s mind can be compared to an iceberg. At the tip of the iceberg, or the conscious mind, exists all the emotions and perceptions that one is aware of. However, underneath the water, the mass of the iceberg represents the unconscious mind, housing unseen fears and desires. However, these fears and desires surface not through real world actions, but rather through dreams and lurking thoughts. Like many, Miller has experienced isolation in the past, however his innate fear of loneliness has arisen from his unconscious mind in the form of dreams.

“It’s a shooting star!”

A young girl gasps in unadulterated excitement. A cheshire smile spreads over the expanse of her face, cheeks tinged pink from the cold and glistening eyes that reflected the stars gracing the sky above her.

Slowly, she rolls onto her side as her eyes skip past her mother and glance at the two figures resting besides her on the grass, their bodies still with fatigue. A father and sister, sleeping quietly in comfort.

But as her eyes begin to trail back to her sleeping mother beside her, they instead find empty space.

Redwood High School student Julia Smith, whose name has been changed, has had the same recurring nightmare since the first grade. Once a week, the same image of her family’s death is replayed, and the blame falls on Smith in each nightmare.

She lifts one foot in her dream, experimentally taking a step towards her home and testing the stability of both the Earth and her own body. Her feet repeat the action until she reaches the entrance. Inside, her home is shrouded with silence, void of laughter and conversation.

Slowly, she leans against the nearest door as the wooden frame begins to creak open. But suddenly her body shakes with violent force and she drowns in terror. A body lies near the entrance to the small room. It no longer radiates heat or energy or warmth, instead emits nothing.

Her quivering eyes cast downward and rip their gaze from the figure in a desperate attempt to erase the image imprinted on her retinas, only to read an accusatory note that sets her entire body on fire.

The girl scrambles to her feet, wiping at the burning tracks of tears that spill along her cheeks. She wills for her legs to move faster, for the muscles that threatened to cramp and collapse to carry her body back outside and away from the bitter sight that now plagues her thoughts.

But she is only met with the still bodies of her father and sister. Not from sleep anymore, but rather from lack of breath, and with the same horrific message etched onto them.

“Written on both of [my father and sister] is ‘You did this,’” Smith said. “[The dream] always ends with me being taken away and held in a cell.”

One can’t help but question what causes the emergence of such graphic and vivid nightmares. What is their origin, why do they reappear throughout one’s life and how can one liberate themselves from the weight of these horrific visions? Typically, recurring dreams appear as a response to unresolved stress. In Smith’s case, an everlasting fear of loss is recurrent in these nightmares, as seen when her family is taken away within each dream. This separation from her family also elicits self-blame, as Smith is held accountable for the deaths of her loved ones, although she is unaware of the reasons why the blame is shifted in her direction. The origin of this recurring delusion is unknown to Smith, and hinders her ability to find the cause and amend it.

Consequently, these weekly dreams continue to haunt her, regardless of the countless methods she attempts in an effort to stop them.

“I’ve tried several different forms of therapy, such as individual, group, EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing), and several others,” Smith said. “I’ve also done several sleep studies and have been on medication.”

Many use therapy as a means to solve or discuss their issues, often gaining a clearer mind after a session. But with Smith, therapy, along with medication, have not been successful in preventing these grisly dreams. This suggests that the fear is deep rooted, and given that these nightmares appeared in her early youth, it could extend to an issue that made an impact on Smith as a child. “The meaning of a dream doesn’t just depend on symbols and content; it depends on a person’s individual experiences, their feelings and views, and the timing of the dream,” said Dr. Rubin Naiman, a professor and dream specialist at the University of Arizona.

Not only do these nightmares take a toll on Smith’s quality of sleep, as she would consistently wake up in tears, and occasionally scream in her sleep as the nightmare progresses, but her daily routine is also disrupted.

“[The nightmares have] made it hard to get up and have a normal day, especially with school,” Smith said. “[The nightmares] also just put me in this weird haze, making it hard to interact with others.”

“It was just one or two would wobble, and they’d fall off.”

A single tooth twitches then twists, sending shooting pain through his jaw. The tooth scrapes against his surrounding teeth then tears itself away from the gum, dangling by a thread. Metallic, tangy blood blossoms across his tongue. The first tooth tumbles out, then two more follow, tumbling out of his gaping mouth like raindrops landing softly in his palms. His tongue frantically flickers over the holes, feeling out the new, unfamiliar landscape of his mouth. Tooth after tooth twitches and detaches from its root, rolling out like small pebbles into a pile. He chokes on the teeth, spitting them out and desperately running his tongue over his bare gums.

Suddenly, he jerks awake to a blanket of still darkness. He props himself up, feels teeth sliding down his shirt and immediately looks down expecting to see bloodied teeth, but sees nothing but the smooth fabric of his shirt. He coughs and forcefully swallows, trying to wash away the strangling feeling of something stuck in his throat.

“These dreams became so real that [when] some of my teeth would fall on my shirt or in my throat, I will wake up feeling something,” said Bob Zhu, a Paly junior.

His hands maneuver their way through the darkness, reaching up to his mouth and neat rows of teeth until he is confident they are present.

Recurring dreams of losing teeth carry various meanings and are one of the most common dreams. “Dream Motif Scale” a study by Calvin Kai-Ching Yu conducted in 2012 aimed to find an assessment tool for measuring the incidence of dream motifs; 39 percent of respondents reported that they had experienced their teeth falling out in dreams at least once. These dreams are thought to be associated with feelings of anxiety; as teeth are a significant part of one’s physical appearance, losing them can be linked to anxiety regarding the way others perceive you. Negative emotions such as pain, guilt and stress could also be the cause of these dreams. They started occurring when Zhu’s golf season began and, with both golf and schoolwork, his schedule became packed, causing him to become stressed.

During this time, Zhu started experiencing additional recurring dreams filled with enormous waves. He opened his eyes to find himself standing on the edge of a cliff. The frigid icy wind pushes him backwards and he falls, scraping his elbows on the jagged crystalline rock. As faint drops of water meet his eyelashes, he looks up and immediately reels backwards at the colossal wave looming above him. Moments later, the water careens downwards, and all he can do is stare. The wave crashes on the edge of the cliff, inches from his toes, rebounding and showering sheets of water over him.

The numbing water seeps through the cloth and his skin, seeming to touch bone as his teeth chatter, rattling in his skull. He squeezes his eyes shut as he shivers uncontrollably, engulfed in darkness and numbing water until the darkness slowly gives way to airy yellow light. His eyes flutter open and warm yellow rays of sunshine illuminate his face in the early morning light. He gently touches his arm, still tingling from the icy water, and combs his fingers through a tangled mass of hair, surprised to find it’s dry. He slides out of bed, rubbing his head and pondering the dreams he had that night.

“In the language of dreams, water often represents our emotional life, the feelings we have under the surface, while the solid ground represents what we knowingly communicate to others,” writes Cynthia Richmond in her book, Dream Power: How to Use Your Night Dreams to Change Your Life. Water is one of the most common symbols found in dreams, as large waves and tsunamis are associated with overwhelming and threatening negative emotions that have been ignored. These emotions may swell up after being suppressed, eventually taking on the form of a huge wave related to the dreamer’s anxiousness over perceived negative future events.

“The joy of realization woke me up,” Zhu said. These two dreams occurred over and over again until one night, in the midst of the chaos, the unlikeliness of the events dawned on him. Convincing himself it was only a dream, he woke up and found himself back in reality. After this realization, the dreams suddenly stopped.

The impact of influential dreams extends beyond the lives of singular individuals. It has also played a role in the origins of various world religions. Freud’s theory of dreams includes the aspect that religious beliefs are a result of dream-stimulated illusions and delusions. In many spiritual and religious contexts, dreams are celebrated and are seen as a connection to a “greater force.” These mysterious and mystical experiences generate a sense of awe and wonder, particularly when theses dreams include visitations from the dead. Deep existential questions typically arise from this, including ones about the soul, the afterlife and supernatural realms. This leads to the personal interpretations of these dreams which shape individual religious beliefs as a form of explanation. These religious connections can also generate fear and reluctance to sleep for those who experience terror in their dreams. For instance, in the Catholic religion, a recurring nightmare can be seen as an interaction with the “devil.”

For Jane Rennen, whose name has been changed, a combination of a recurring nightmare, featuring a shadowed boy with an inhuman smile, and sleep paralysis has haunted her since childhood, souring her relationship with sleep.

Seven-year-old Rennen sits upright on her bed, tense as she waits for her mother to dip her fingers into a bowl of holy water. Finally, the familiar coolness of the water meets her fingertips and, with a flick, her mother sprinkles drops across the pale walls of her bedroom. The water trickles down the walls, pooling into rivulets and collecting in the corners of the room. After a quick kiss goodnight and a reassuring smile, her mother walks out of her bedroom, leaving Rennen to pray for just one peaceful, terror-free night of sleep.

She lays on her back for almost a minute before her trembling hands dare to reach out and pull the covers up to her chin. Now she closes her eyes, and immediately the darkness seeps into the back of her eyelids, imprinting itself on her brain.

Suddenly, her eyes are open again and she catches a flicker in the corner of her eye. She desperately tries to yell, but she can’t move, can’t stop her rapid breathing and can’t do anything but watch as the shadow flickers once again before emerging from the folds of darkness.

“It’s the thing that made me an insomniac; I would rather stay up all night if it meant I wouldn’t have to experience the horrors of the night,” Rennen recalls. Sleep paralysis sufferers, can see and feel all of the emotion that comes with a nightmare, but they are unable to control their movement and breathing, leaving them to watch their own nightmare. It is a horror to experience the same nightmares over and over, while being forced to simply watch the experience. Left without an escape from her nightmares and unconscious sleeping, Rennen briefly turned to religion as an explanation and a coping mechanism for her condition.

“I thought it [the boy] was the devil coming to get me, which is why I prayed every night. It got to the point of my parents sprinkling the walls of my room with holy water,” she said. When Rennen was younger, she would often get a glimpse of a little boy with a sadistic smile, who would walk closer and closer to her until he was leaning directly above her. The vision does not stop there, however, as she would also experience the boy wrapping his shrouded fingers around her, as if to choke her.

But, her relationship with the experience has changed over time. The shadow has expanded from solely being a little boy to taking other forms, such as grown men and women. She does note that they all have glowing eyes and lean so close to her face that she could practically feel their breath on her skin.

Simply learning more about her condition has also changed how Rennen experiences the dreams. After her diagnosis, she knows that she suffers from sleep paralysis, but that knowledge still does not help her during the nightmares. “It’s all I can see, all rational thought escapes me and I just want it to be over,” she said. While the terror of the moment is consistent with what she experienced as a child, Rennen has also learned to adapt to the condition and lead a relatively normal life by using coping mechanisms to ward off the nightmares.

“I actually sleep a healthy amount now, and I usually cover my head with blankets to keep myself from experiencing [the dreams],” Rennen said. Although covering her head with blanket usually blocks out the shadows that frequently haunted her sleep, there are still instances where the figures once again invade her sleep and fill her with the all-too familiar terror.

As she has matured, she has shifted her mindset on the disorder. “I think a lot more rationally about it and remind myself it’s normal,” she adds.

Despite the adaptability some people possess, those with sleep paralysis often experience terrifying moments that lead them to even fear sleep, as demonstrated in Rennen’s earlier experiences. “Not being able to move or speak or do anything while you feel like someone’s choking you or whispering scary things in your ear is hell on Earth,” she said.

Now, imagine that your paralyzing dreams and muted screams occur in a place other than your bed. Instead it is in the light of day, as paralysis abruptly consumes every muscle and bone while you walk down the street with your friends or stand in line for coffee. For 36-year-old Palo Alto resident Arun Wright, this is the reality of dealing with sudden cataplexy attacks, which strike at unpredictable moments throughout the day. Cataplexy is a subcategory of the broader sleeping disorder narcolepsy, which refers to the chronic neurological disorder of excessive and uncontrollable daytime drowsiness. The common symptoms of cataplexy describe an attack on the body in which strong emotion, particularly joy, causes the sudden collapse of the limbs and muscles while still remaining conscious. Wright has been living with this disorder since his mid-twenties and regularly takes medications in order to limit these types of cataplectic attacks.

“For me, it happens when I think I’m being really witty and getting positive feedback from others,” he said. “Usually, if I’m standing up I will literally just crumble to the ground. Like a rag doll. And I’m fully conscious the entire time but I can’t control anything. I can’t speak, I can’t open my eyes. My eyes usually roll back. People say it’s really creepy looking.”

According to National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the condition is caused by a lack of the chemical transmitter hypocretin in the brain, which is responsible for regulating the sleep-wake cycle. Often, the deficiency occurs when the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the portion of the brain responsible for producing this chemical transmitter. “You’re literally trapped in your own body,” Wright said. “It’s bizarre.”

Like many with cataplexy, Wright has had to search for work that cooperates with his sleep schedule. This has proved a challenge, as he has to make time for multiple naps throughout the day. However, he occasionally experiences episodes while functioning regularly, although he is technically in a sleeping state. “If I were to fall asleep while talking to you, I could continue having the conversation,” Wright said. “And then I would wake up and have no idea what we were talking about. This happened recently: I was visiting my parents in North Carolina and fell asleep in the passenger seat on the drive home.” He remembers sleeping, but his parents recall having a conversation the entire time. Although these disorders have majorly impacted Wright’s life and have led to an extreme alteration in his lifestyle, he has been able to achieve a state where the symptoms are controllable. “I’ve had it for so long now, but the last years have been pretty stable because I’ve found a routine,” he said. “But it was definitely jarring at first.”

There is a common correlation for many between the frequency and vividness of one’s dreams and the amount of sleep they dominate. It has been said that the less consistently one sleeps, the more graphic and extreme one’s dreams will be. This is because of the body’s natural sleeping cycle of rapid eye movement, or REM, which is when dreaming and increased brain activity occurs. This cycle typically occurs every 70-90 minutes after one falls asleep, however a lack of sleep can cause the cycle to start much sooner in order to make up for lost time and to intensify the dreaming process.

Cataplexy causes the muscles to collapse, while maintaining consciousness due to strong emotions. On the contrary, insomnia sufferers have trouble falling asleep, and those with it often lie awake at night for hours. In the case of insomnia, the dark doesn’t offer the same comfort and rest that it gives to others. Rather, it almost resembles a prison cell, the night consisting of tired eyes pointed towards the ceiling and a desperation for the soft hush of sleep to eventually wash over.

Tuning in on the sound of your clock’s hand ticking becomes routine, the faint click humming through the air. You’re surrounded by darkness that’s only seen when your eyelids flutter closed, and yet here you lie, trapped in a facade that, at first glance, appears like sleep—but is instead fatigue. Lifting your head slightly, you glance at the circular device.

3:43 a.m. it reads, and you can’t help but slam your skull against the flattened pillow, its cushioning capability diminishing as every minute drags by. Every bone in your body aches for the pull of sleep, but your brain will not allow it. Restless nights filled with tossing and turning makes for a torturous cycle of living, a cycle induced by a common sleep deprivation disorder affecting 30 million Americans per year: chronic insomnia.

In contrast to acute insomnia, which only presents itself at times of distress, chronic insomnia relates to disrupted sleep occurring at least three nights per week for a minimum of three months. Abby Sullivan, a junior at Gunn High School, has experienced chronic insomnia for around two years, but was only fully diagnosed last May. For her, the inability to fall and stay asleep impacts many different aspects of her life. “Insomnia has made my life really hard in a lot of ways,” Sullivan said. “It’s hard on my mental health. My doctors and parents are always on me about how much sleep I get, but I feel like it’s something which I can’t completely control.”

She adds that she tends to wake up from sleeping anywhere from two to seven times per night, ranging from around a few minutes to over an hour. “I used to have trouble falling asleep, but now I have trouble staying asleep. I went through a period where it didn’t matter if I went to bed at 10 p.m. or 3 a.m., I would still wake up at 5 a.m.” The National Sleep Foundation has reported that most insomniacs experience several different symptoms as a result of their lack of sleep, including mood disturbances, fatigue, difficulty concentrating and a decrease in energy and performance throughout the day.

Sullivan’s sleep troubles aren’t that uncommon, of course, nor are any of those documented here. Healthy sleep, like any precious commodity, is sometimes difficult to find. And restless nights often lead to sleepy days.

“I’m really just constantly exhausted,” Sullivan said. “It’s like an iPhone. If I only get a 35 percent charge, I can only do so much with that small amount of energy.”