Monster in the Mirror

An inside look into the complex topic of eating disorders and the stories of three paly students who have fallen victim to this mental illness. DISCLAIMER: This story includes sensitive content relating to the topic of eating disorders and body image. If you have struggled with either of these, please read with discretion.

March 17, 2017

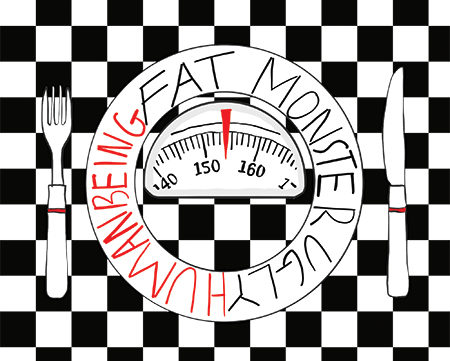

She’s so skinny, she must be anorexic.” “He’s huge, why doesn’t he go on a diet and hit the gym?” Comments like these are made online, in schools and on the street every day. When someone looks overweight, that is not an invitation to assume they eat fast food and never exercise. Likewise, those who are very thin may either be congratulated for being fit and healthy even though their health may be a serious concern, or are criticized for being “too small.” While it might be easy to judge someone’s mental and physical health based on their appearance, these misconceptions regarding other’s health can be detrimental to their self-esteem and body image. Eating disorders are incredibly common and have the highest mortality rate of any mental illness. People of all cultures, races and gender identities suffer every day in silence, unaware that they can have an eating disorder without looking skeletal.

She’s so skinny, she must be anorexic.” “He’s huge, why doesn’t he go on a diet and hit the gym?” Comments like these are made online, in schools and on the street every day. When someone looks overweight, that is not an invitation to assume they eat fast food and never exercise. Likewise, those who are very thin may either be congratulated for being fit and healthy even though their health may be a serious concern, or are criticized for being “too small.” While it might be easy to judge someone’s mental and physical health based on their appearance, these misconceptions regarding other’s health can be detrimental to their self-esteem and body image. Eating disorders are incredibly common and have the highest mortality rate of any mental illness. People of all cultures, races and gender identities suffer every day in silence, unaware that they can have an eating disorder without looking skeletal.

There are two types of eating disorders that typically come to mind: Bulimia nervosa and Anorexia nervosa. Clinical psychologist and assistant professor at Stanford, Cara Bohon, explained the new way in which eating disorders are diagnosed, characterized and categorized. Mental health professionals use a diagnostic and statistical manual to classify different categories of mental disorders, the most recent version being DSM-5. In this version, some of the main eating disorder categories include Anorexia nervosa, Bulimia nervosa, Binge Eating Disorder and Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED), in addition to Childhood Feeding Disorders; however, those who do not meet all of the criteria for these categories are placed in existing subcategories.

Eating disorders consume the lives of millions of people around the world. According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, at least 30 million people suffer from serious eating disorders in the United States, not including those who are undiagnosed. Although eating disorders are common, especially among preteens, teens and young adults, many go unnoticed and untreated — something incredibly dangerous.

The following stories of three Palo Alto High School (Paly) students, whose names have been changed to protect their identity, illustrate how each struggle with various eating disorders is unique. The struggles of these three students exemplify the disparities between the types of disorders that exist and identify the complexity of issues relating to body image, food or both. Here are their stories.

Isabelle’s Story

Isabelle never suspected she would suffer from two different eating disorders in succession. She grew up with a fast metabolism and never worried about what she ate. Like any kid, Isabelle loved sugar, eating sweets whenever she could get her hands on them. Things changed over the years, and Isabelle would eventually fall victim to both Bulimia nervosa and Anorexia nervosa.

Last summer, Isabelle started to suffer from Bulimia nervosa, an eating disorder characterized by the act of throwing up previously consumed foods. Isabelle knew what she was doing was not normal, but her mindset created by her eating disorder took over and told her throwing up was necessary. With the arrival of summer, Isabelle began cutting out sugar in an attempt to “clean up” her diet to obtain a more perfect “bikini body.” She had been following different YouTube and Instagram stars who followed a vegan diet, and decided to try it out.

“I thought it was really cool, so I tried to go vegan for two weeks and I was successful … after the two weeks, I went to Mexico and I was super scared to start eating meat again because … I had lost a little bit of weight.” Isabelle’s diet triggered her eating disorder; the idea that she had lost some weight by eating “healthier” made her believe that reverting back to her normal eating patterns would result in gaining the weight she had lost. Isabelle’s fear of weight gain was so paralyzing that she would make herself throw up the small amount of food she ate. “I knew I had an issue and I tried to stop throwing up, and it would go from throwing up a couple times a week, to everyday, to once a day, then a few times a day … and it got to a point where I just couldn’t stop,” she said.

It was not until later that summer when Isabelle went on another trip that she was caught purging. “It was the most traumatic thing that has ever happened to me. Luckily, I got caught at the beginning of the trip, so I was able to eat more while I was there.” Isabelle was supervised for the rest of her trip and was fed the amount she needed to regain some of the weight she had lost over the two months she had been purging in order to maintain a healthier weight.

It was not until later that summer when Isabelle went on another trip that she was caught purging. “It was the most traumatic thing that has ever happened to me. Luckily, I got caught at the beginning of the trip, so I was able to eat more while I was there.” Isabelle was supervised for the rest of her trip and was fed the amount she needed to regain some of the weight she had lost over the two months she had been purging in order to maintain a healthier weight.

Once Isabelle returned home, she knew she had gained weight. Although she had stopped throwing up, she was not able to return to normal eating habits. “I had gotten into the habit where I had a weird relationship with food,” Isabelle said. She religiously counted every calorie she consumed to ensure she did not go over her limit for that day. Her hunger cues, such as her stomach growling, slowly started to fade to the point where her body was not giving her the proper signals to eat. She stopped eating breakfast and would never eat with her family because she did not know what was in the food her mom cooked.

Isabelle expressed the worst part of both her eating disorders: “Guilt was the worst thing for me because whenever I would eat a good amount of food I would feel so guilty.” Racked with guilt and fear over what food would do to her shrinking body, Isabelle continued to fall deeper into a caloric deficit.

During the time period that Isabelle was restricting her calorie intake, her exercise habits changed as well. “I would exercise to burn calories, not to just exercise.” She stopped seeing friends because of her anxiety over what they would eat and how she would hide her issues. Food and body image took over Isabelle’s life and stopped her from being the happy and carefree person she used to be.

Isabelle, like anyone with an eating disorder, had unique thoughts that influenced her desire to throw up and restrict her calorie intake. Her eating disorders were a voice in her head making her fear “unhealthy” food. There are many misconceptions about eating disorders and what they really are; Isabelle admits that even she had a specific idea about eating disorders that was shattered when she experienced one herself. “The stories I had always heard about Anorexia were that people would eat like 300 calories a day and that was not my case. I had associated Anorexia with sickly thin people, and I don’t think I was ever sickly thin and scary-looking.” Isabelle’s message is to not let one’s appearance fool them into thinking they do not have an eating disorder. Now that Isabelle has been diagnosed, she is monitored by doctors and has been going to family therapy.

When Isabelle went to an eating disorder clinic, she was officially diagnosed with Anorexia nervosa. People with Anorexia nervosa are typically characterized as low-weight within the context of their health history and demonstrate behaviors that suggest a fear of gaining weight or becoming fat. Patients also tend to have an altered perception of the seriousness of their problems.

Recovering from an eating disorder is a different experience for each individual. Some habits formed from eating disorders never fully disappear; instead, they slowly fade from the center stage of one’s life and become background noise. It is typical for those who are going through recovery to have all control over food taken away from them.

Health looks different for everyone, and medical professionals are the only people who have authority over what is a healthy body. Once the body is back to a healthy place, therapists and doctors then help guide the mind to return to healthier habits as well.

Many therapists use the concept of having a “wise mind” to help explain to patients how they can challenge the distressing thoughts.

Isabelle has a lot of hope for the future. When asked what advice she would give to other people struggling with eating disorders, Isabelle said: “Get help now, because I know I didn’t tell anyone for a couple months, and if I hadn’t gotten caught, who knows where I would be today?”

Emily’s Story

Although she was never officially diagnosed with a specific eating disorder, many close friends grew worried about Emily’s lifestyle after social issues arose at the beginning of her junior year. Emily’s obsessive lifestyle consisted of strict diet control and excessive exercise. While many may commend that behavior as motivational and healthy, her change in lifestyle, combined with insecurity and depression, quickly spiraled into a serious cause for concern.

Emily was rapidly overcome by insecurity and hatred for herself and her body. She became convinced that she was obese and unattractive, and that, no matter how many times they attempted to reassure her, her friends and family believed this about her as well. “I began to hate my body, my looks, my stomach, my legs, my arms, everything … I do not ever think I will be at a point where I will absolutely love the way I look,” she said.

Consumed by a fear of developing a larger body type and in desperate need for an outlet from stress, Emily reached a point where she was exercising in the morning and after school almost every day. That, combined with her selective diet, was an undeniable threat to her health.

“Once, after starving myself for two days, I decided to walk the dish, and on the first hill, I fainted and fell down. I felt very dizzy and nauseous,” she said.

Although she was able to recognize that her self-perception was negatively impacting her health, she continued this regimen for months, turning to seemingly “healthy” outlets such as fitness and nutrition because she was haunted by the belief that she was overweight. Emily was tormented by her unstoppable self-deprecating thoughts and a desperation to change her appearance — controlling her diet helped bring her temporary satisfaction.

“I am too obsessed and controlling over what I eat and feel down whenever I eat junk food. Counting carbs, calories, sugar and fat gets very difficult because all of these elements are in all foods, but it has to be done in order for me to feel satisfied,” she said.

Despite having never been bullied for her body or appearance, Emily admits that she has felt negatively influenced by those who surround her every day. “Three out of my four best friends are very, very skinny girls. When they complain about their body or stomach or one teeny tiny pimple on their face, it makes me feel that much worse about myself,” she said. “I know I shouldn’t be influenced by others, since in the end all I care about is being satisfied with myself and not someone being satisfied with me, but it is hard to focus on myself when I feel like everyone is more attractive and skinnier than me.”

Despite having never been bullied for her body or appearance, Emily admits that she has felt negatively influenced by those who surround her every day. “Three out of my four best friends are very, very skinny girls. When they complain about their body or stomach or one teeny tiny pimple on their face, it makes me feel that much worse about myself,” she said. “I know I shouldn’t be influenced by others, since in the end all I care about is being satisfied with myself and not someone being satisfied with me, but it is hard to focus on myself when I feel like everyone is more attractive and skinnier than me.”

After a couple of months, Emily began to notice changes in her physical appearance, but after realizing she was still unsatisfied with herself, she decided to see an ACS (Adolescent Counseling Services) counselor at Paly to help her talk through her struggles with body image and food. However, she admitted that the counseling services were mostly just a safe space where she could express her feelings without judgement and didn’t see much improvement.

Emily never looked like skin and bones, she simply appeared more “fit” — her body became more toned and muscular, so those who didn’t know about her battle with food praised her for her progress, and that is exactly why Emily’s struggles are so complex; as Bohon said, “you can’t see health.”

Although Emily has never been diagnosed, it is apparent that her habits raise health concerns; she changed her diet and began to exercise obsessively with the sole purpose of changing her body and losing weight. She was obsessed with her scale, and hated herself to the extent that she felt the need to take drastic health risks to alter her body type. Emily now feels that her habits are healthful because she genuinely wants to improve her athleticism and has fewer diet restrictions for herself.

It is evident that Emily still restricts herself, and some may argue that her lifestyle is not yet truly healthy because her meals don’t appear to be balanced. The improvement, however, lies in her purpose — her intention has shifted from wanting to change the way her body looks to wanting to improve her athleticism. Still, Emily has not completely overcome her insatiable need to burn the maximum amount of calories or transform her body to correspond with her ideal definition of “fit.” Because of this, her complicated relationship with food continues, although she is currently taking action and trying to improve her mindset regarding the concept of health by talking through her issues with trusted counselors, friends and family. She plans on majoring in nutrition in college with the goal of educating herself on the subject and allowing her to also help others who grapple with this issue.

Kate’s Story

The morning of the first day of second-semester junior year was the beginning of the worst semester of Kate’s life. That morning, her mother found out she had an eating disorder. Kate’s breakfast ended up in the toilet, like many before. Only this time she had forgotten to flush. When her mother discovered the vomit in the bathroom, she immediately knew what was wrong. Little did Kate know, her mother had been bulimic as a teenager and understood exactly what Kate was going through. But before Kate’s mother could tell her that, she rushed off to school, avoiding any confrontation or discussion about her eating disorder.

Once back home, Kate denied that she had an eating disorder. Yet, as much as she tried to tell her mother that she was fine and that it was just a “one-time thing,” her mother knew that this was an illness that wouldn’t solve itself without medical attention. In addition to being bulimic herself as a teenager, Kate’s grandmother had also suffered from Bulimia nervosa and her cousin had an eating disorder as well.

Those who have Bulimia nervosa typically go through binge and purge episodes, and their binges include large amounts of food in a two to three hour time period. During a binge, people feel a loss of control and cannot stop putting food into their mouths. After a binge, bulimics will throw up their food either by self-induced vomiting, laxatives or diuretics, which is known as a purge. Similarly, people who binge and then do not throw up can also compensate

for the food they consumed by excessively exercising or fasting and skipping meals. Patients who participate in this behavior on average once a week for three months or longer meet criteria for Bulimia nervosa.

Although Kate had some of these symptoms, she did not consistently binge and purge. Rather than being diagnosed with Bulimia nervosa, Kate’s doctors instead determined that she had EDNOS (Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified), an eating disorder that meets criteria for multiple categories, such as Bulimia and Anorexia nevosa. Since the time Kate was diagnosed, the term EDNOS is no longer used by the medical profession. Nonetheless, we will continue to use it here because it was the specific diagnosis Kate received at the time.

Instead, the new “catch all” category is called OSFED. OSFED is the diagnosis for those who have a psychological problem relating to food and fall within one of five specific subcategories of eating disorders: Atypical Anorexia nervosa, Bulimia nervosa of low frequency or limited duration, Binge Eating Disorder of low frequency or limited duration, Purging Disorder or Night Syndrome. If a patient still doesn’t match the criteria for any of those five subcategories, they are diagnosed with Unspecified Feeding or Eating Disorder (UFED), indicating that there is clearly an issue present but not enough is known to categorize what it is.

Kate’s struggles with her eating disorder began about a year and a half ago when she went to her pediatrician for a normal doctor’s visit. The appointment was like any other check-up, but this time, her doctor told her that she was seven pounds heavier than at her last check-up. Her pediatrician asked her about her eating habits and, like many other people her age, she informed him that she ate dessert every night. Kate’s doctor suggested that she should only eat dessert once a week. Little did that doctor know, this conversation was the start of Kate’s unhealthy obsession with her weight. Kate had been studying eating disorders at school, and after this conversation with her doctor decided to give purging a try. One night after eating a big dinner, Kate induce vomiting and was relieved to have erased that evening’s calories. From that evening forward Kate began to employ a range of unhealthy techniques to control her weight. She would purge, exercise excessively and restrict her food intake.

Kate’s first step to recovery came a year and a half later, after her mother discovered the telltale signs of her illness. Kate met with her pediatrician, who quickly helped her find a therapist, dietician and an eating disorder specialist. She sees her dietician every other week and works with that doctor on her relationship with food and her overall nutrition and eating habits. She goes to her therapist weekly (finding the right therapist took quite some time but now Kate has a close relationship with her therapist, which has been hugely helpful). Lastly, Kate sees her eating disorder doctor. She meets with this doctor every three weeks to check in and make sure she is recovering. Urine samples, weight checkups and taking vitals are just some of the many processes and tests Kate has to go through while at her triweekly eating disorder doctor appointments. Thanks to these numerous appointments and meetings throughout the past year of her recovery, she is continuing to make progress in controlling her illness.

To begin her recovery, Kate needed to understand why she saw food differently than someone without an eating disorder. In Kate’s brain, food was to be avoided. Food was no longer pleasurable; it felt like a poison which needed to be expelled from her body. As Kate put it, “[to me], lunch is not normal to eat, which obviously I know logically is not true, but the voice in my head keeps telling me…that eating, in general, is not normal, not healthy. When food goes into my body, I’m like ‘Oh I have to get it out, it’s not normal to be eating.’”

What’s worse, Kate’s struggle was twofold. Not only did she need to force herself to eat, but once she was able to get the food into her system, she had to fight her urge to throw it back up. A huge part of Kate’s recovery has been retraining her brain to view food differently and to understand that eating is normal. One of Kate’s exercises to retrain her brain is to know her intentions before she starts eating. Every time she sits down to eat, Kate goes through a set thought processes. She asks herself, “Why am I eating lunch?”, then consciously walks herself through the idea that “lunch is normal, [and] everyone needs to eat lunch.” She is making good progress, but there are still many doctor visits and checkups in her future.

Kate knows that eating disorders are mental illnesses and that there is no quick fix. As she has gone through this journey, Kate has also come to realize that a lot of work goes into healing from an eating disorder.

“Recovery is not easy and it doesn’t happen at the flip of a switch. I’ve been working at it for a year and a half and I’ve given up so many times. You don’t just choose to recover, and then everything turns back to normal. You have to choose recovery every day, at every meal, and it’s not easy.” It may not be easy, but like her mother and grandmother before her, Kate is on the path to reclaiming her healthy life.

Health is not something that you can see. Although someone may appear healthy on the outside, they are not necessarily healthy on the inside. Someone may be suffering from an eating disorder and you may not even know it, because eating disorders are mental illnesses — what can be seen with the eye is not a measure of health.

Health is not something that you can see. Although someone may appear healthy on the outside, they are not necessarily healthy on the inside. Someone may be suffering from an eating disorder and you may not even know it, because eating disorders are mental illnesses — what can be seen with the eye is not a measure of health.

The effects and symptoms of eating disorders are unique to the person and their situation. Bohon suggests that one of the first steps towards general body acceptance is separating thoughts about food from body image. “…Food is something that nourishes you, …it is also delicious, it is something that we use in a social way, it is multifaceted, so to have it be intrinsically tied to body image diminishes all of the things that food can be. If we think of food as our fuel it can have a really positive connotation, if we think of [it] as celebratory it can have a positive connotation there, as something to have fun with and experiment with new recipes it can also be something that is pleasurable and enjoyable,” she said.

Once food is separated from the idea of body image, the focus changes to taking steps towards body acceptance, which start with retraining the mind to appreciate “what your body does, not how it looks.” Another method she suggests is to take steps towards changing what is considered ideal. Whether intentional or not, expectations related to appearance are marketed to us every day, and by changing our reactions to body complaints or harmless comments we can slowly retrain our mind to reject these ideals.