Passing Judgement

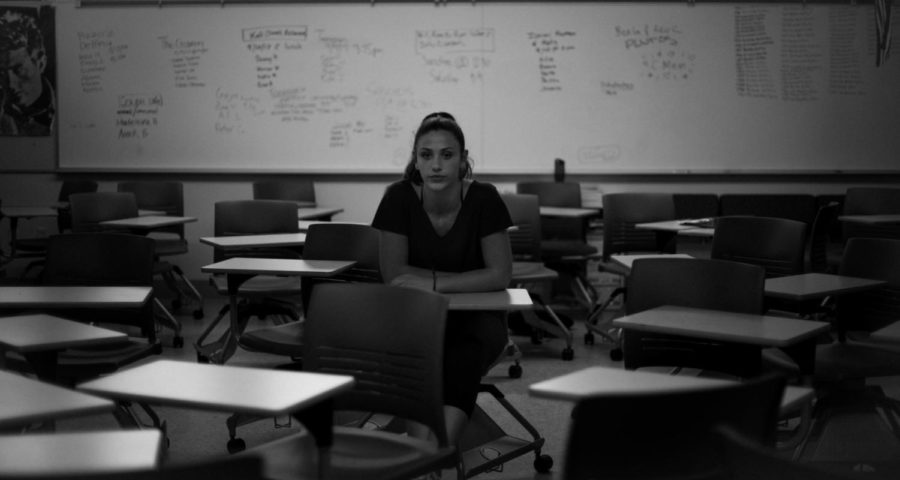

A reflection on being white passing and the ignorance I have experienced within my community

My dad is black and my mom is white, but I have white skin. I am white passing. Racial passing is when a person who appears as though they are from one racial group actually belongs to another or multiple racial groups. Although I was aware my dad is black and my parents stressed to me that I am also African-American, up until middle school I thought of my race as white since that is the color of my skin. But now I’m not so sure it’s as simple as that. Half of my identity has gone unnoticed for many years, and over time I have begun to realize the effects on myself, family and others. This aspect of my racial identity has evolved from a burden, due to the varying reactions I have received, to a chance to educate others about an unconventional topic.

Growing up biracial with one ethnicity constantly going unseen has proved to be difficult. One common reaction I continually receive from my peers is that they think I am outright lying or joking about the color of my father’s skin; some people have even asked me for photographic evidence of my dad’s race. Although this is a recurring response, it has never ceased to weird me out–why would I lie about that? Is that something people really joke about? The worst part of this encounter is having to defend myself. Not only is it an awkward thing to do, but I am never sure of what to say; do I have to provide some kind evidence of my “blackness”? Or do I just let them think what they want? I’ve learned to go along with it and describe my father’s personality as a means of humanizing him. I want to ensure that they do not just take away the fact that he is black, but that they understand the kind of person he is and the relationship I have with him.

Additionally, often times people decide to dissect my appearance and personality in search of African-American traits. Responses like “Oh I kinda see it, you have black-people lips!” “Does that mean you can twerk?” or “You’re like a reverse oreo, you’re white on the outside but black on the inside–cause you’re kinda sassy.” These things are incredibly offensive to say to a person’s face. Analyzing someone’s race into stereotypical traits invalidates part of their identity. By deciding that certain aspects of my personality or physical features define who I am, people deny me a sense of self and true individuality. It’s as if this part of me is just a set of stereotypical traits people have learned about on TV or social media, and not an actual aspect of my identity.

Most people have the common decency not to say, “Woah you’re black, so that means you can say the n-word, right?!” However, I have still received this comment. Yes, I am half black, and no, it doesn’t mean I can say the n-word. Probably the most revolting part of this response is that this white person almost seems jealous that I, someone who also looks white, might be allowed to say the n-word. Personally, I am not at all comfortable saying the n-word. It is something that has been taken from being used as a derogatory term by white people towards the black community, and turned into a word that carries connotation of camaraderie within the African American culture. Since I have benefitted my entire life from white privilege, it feels wrong to use that word when I haven’t experienced half the struggle of someone living with darker skin.

One of the continual hardships that the black community faces that I, as white passing, have never had to face is having a complicated relationship with law enforcement. Many parents of black children have to talk to their kids about how to deal with the police even if they are not delinquents. One day when I was in the car with my dad and my older sister, who also has black skin, he began to tell her that if she comes in contact with the police she must stay quiet, be overly respectful and be careful of everything she does. At the time, I didn’t think about it too much because I assumed it was just a conversation any parent would have with their 16-year-old. However, I have never received such a talk because authorities don’t assume that I am a threat.

Even though I do have white privilege and a majority of people would not suspect that I am part African-American, it is still a part of who I am. I know that being black has affected my father his whole life and, because I’m white passing, I’ve been able to witness people’s small biases and poorly covered-up prejudices about black people. I have sat with people who don’t know me very well and will say something they definitely would not have said if there was a black person in the room. Often times, all I can think about are the white people who clutched their bags a little tighter, the policemen who lingered a little closer, or all the store attendants who have watched a little more carefully when they see the 6’2” black man who just so happens to be my dad, walking down the street. My dad is cheesy, loving, and sometimes pretty annoying (as most dads are), but I know that sometimes people see him as a threat. Thinking of this tears me apart because there are so many people who will let an African American man’s appearance dictate what kind of personality he has and what kind of life he lives when he is most likely someone’s loving father, son or husband.

I used to think that maybe the solution would be for me to simply ignore the fact that I’m half black because then I wouldn’t have to deal with these awkward encounters. Now I see the insensitivity of doing this. Half of my family isn’t able to simply ignore their blackness and how, for them, there’s no way to get away from the injustice and continual discrimination surrounding them. Especially in times like this, no one should try to erase aspects of their race, culture or ethnicity that aren’t treated the same as everyone else’s because there are others that don’t have that easy way out of all the bigotry directed at them. Instead, it’s a time to embrace that part and advocate for those who do not have a voice.