Extension of “Exhibit: The Art of Disability Culture”

The stories behind three additional artists at Palo Alto Art Center’s latest exhibit

Don Katz

Don Katz is a potter from Southern California, whose curiosity about ceramics brought him to the Braille Institution of Los Angeles, a nonprofit that provides programs and classes for people with visual impairments.

Katz became blind in 2001 due to bacterial meningitis, an infection of the membranes that surround the brain and spinal cord. “I was in a coma for almost a month,” Katz said. “[I] woke up blind and paralyzed and had to learn how to walk, swallow, feed, bathe.”

After losing his vision, Katz has experienced considerable differences in how people treat him. “You kind of get put in a corner,” Katz said. “Unless someone wants to engage with you, you don’t engage with them, so you feel left out.”

Katz’s ceramics takes an untraditional approach; many of the skills he uses today are self-taught. “I never went to art school,” Katz said. “I’m teaching myself a visual medium as a blind person.”

An important part of Katz’s work is the texture of his pieces. “When I first started, everyone [said] we love the color and I’m nothing to do with it,” Katz said. The texture of a piece allows Katz more artistic freedom. “I want to show that I can make decently symmetrical smooth cylinders, but then I changed the texture,” Katz said. “And for some reason [smooth pieces are] boring to me, [textured pieces are]more interesting to touch.”

Katz wants to be seen and appreciated for his artwork. “I want people to look at me, not as someone who’s blind,” Katz said. “That would be the ultimate goal.”

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”5″ sortorder=”39,37,40,38″ display=”basic_slideshow” gallery_width=”900″ gallery_height=”600″ autoplay=”0″ arrows=”1″]Catherine Lecce-Chong

Catherine Lecce-Chong was drawn to art at a young age, starting painting as a kindergartner. “I think it was that I was looking for beauty,” Lecce-Chong said.

Lecce-Chong has lived with eye damage since birth. “I had to wear these Coke-bottle glasses, and I was teased and bullied and somewhat disabled, although I thought I was normal,” Lecce-Chong said. “I found out in kindergarten that I could paint and that people liked my paintings, so it was a way for me to connect socially.”

Bay Area artist Lecce-Chong was traditionally trained in Western, Japanese, and Asian painting. “When I lost most of my sight later, I didn’t really know what to do,” Lecce-Chong said. “I thought I was kind of finished as an artist, certainly in using the skills I had.”

Painting in bright light hurt Lecce-Chong’s eyes, leading her to paint by candlelight. “One day I was just so dejected that I couldn’t work long hours,” Lecce-Chong said. “We sat down, lit candles to surround the studio and I saw my paintings in candlelight.”

Exploring texture mediums became an integral part of Lecce-Chong’s work after she lost her sight. “When I touched the Braille, I thought, ‘Wow this is so interesting,’” Lecce-Chong said.

Lecce-Chong’s most recent collection, the White Blindness series, was created during the COVID-19 pandemic. “I love them all because they were my friends during isolation, and they still are because we’re still not really totally out there,” Lecce-Chong said.Losing her vision has taught Lecce-Chong that nothing can stop a person from doing what they want, art or otherwise. “Anything you want to do is possible as you can see in the Paralympics,” Lecce-Chong said. “They are athletes, they’re just doing things differently. And I as an artist, I’m just doing things differently. It has nothing to do with disability.”

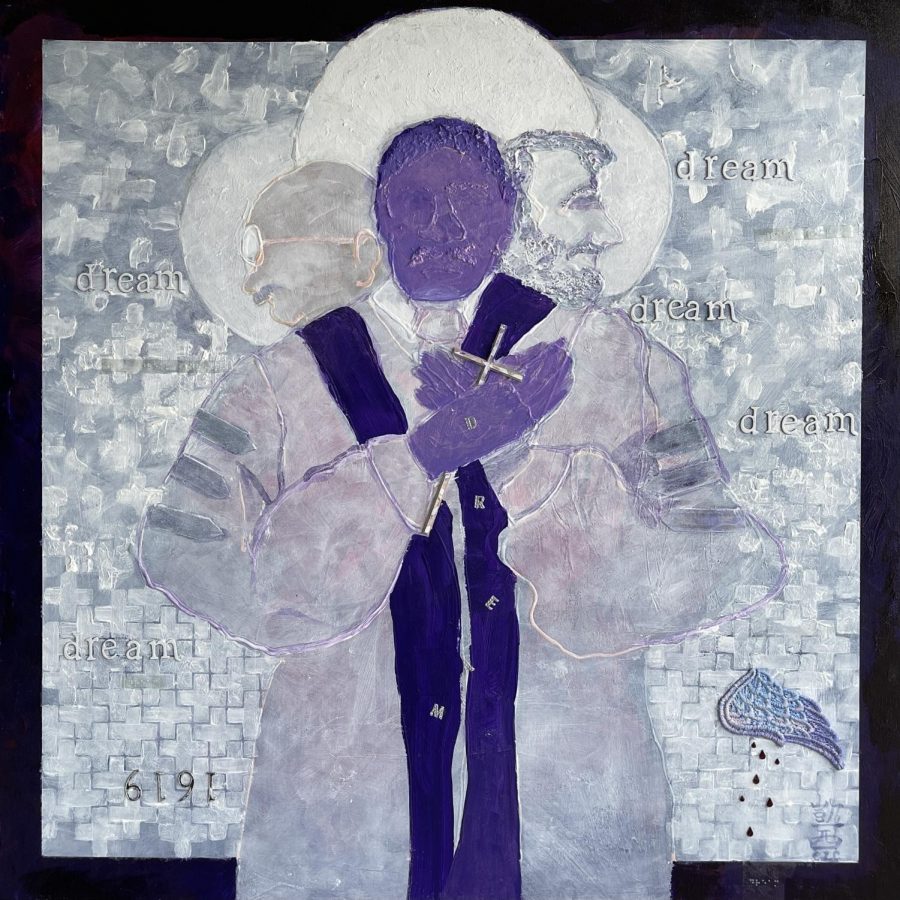

“Cobalt Blue Virgin” by Catherine Lecce-Chong

“Dioxazine Purple King” by Catherine Lecce-Chong

Bill Bruckner

For as long as Bill Bruckner can remember, art has been a significant part of his life. “My earliest memory is being a little under three years old and copying drawings my uncle would draw on a blackboard that my sister and I had in our bedroom,” Bruckner said.

Growing up was not always the easiest for Bruckner, as he did not look like the other kids. “When I was a little kid, I wore an artificial limb on my left side which had a hook,” Bruckner said. “Kids used to tease me and call me ‘Captain Hook.’”

Bruckner has come a long way since then and is now an established artist. He has been using diagonal lines in the majority of his work as he does not have two full arms. “I discovered a really congruent way [to draw] that is most easy and compatible with who I am,” Bruckner said. “I started doing lots of artwork with diagonal lines, and that was really exciting.”

A significant part of his growth as an artist and a person was acceptance. “Part of my growth was coming to terms with myself as a person with a disability and what that meant,” Bruckner said.

For Bruckner, being seen as human is a vital part of acceptance. “My message is that we’re no more special than anyone else,” Bruckner said.

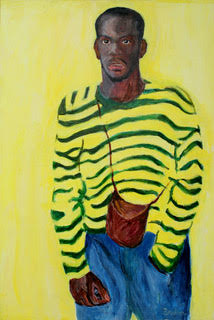

“Portraits of People with Disabilities” by Bill Bruckner

After years of practicing figure drawing, a realization paved the way for his “Portraits of People with Disabilities” series. “I had the realization that none of the models who were posing for the groups had visible or apparent disabilities,” Bruckner said.

By creating this series, Bruckner was able to connect two parts of his life. “It’s a way of both acknowledging and integrating the fact that I’m a person and an artist with a disability into my life,” Bruckner said.

With this series, Bruckner wants to portray the message that people with visible and invisible disabilities are just human. “We’re neither nothing special nor are we pitiable,” Bruckner said. “We don’t deserve your pity, and we don’t deserve your admiration, just because we’re people with disabilities.”

This message is important to Bruckner, as he frequently encounters people who treat his entire existence as something admirable. “There’s been a number of times that the cashier has said to me ‘Wow, you’re amazing,’” Bruckner said. “I always want to think, ‘Am I amazing because I can afford to pay for my groceries?’”

Bruckner wanted to leave his able bodied audience with a lasting impression of his series. “They would feel that they were, in a way, being looked at by the person in the painting like they were sort of as curious about them as they may have been about that individual,” Bruckner said.

“Self-portrait” by Bill Bruckner

“Yvette” by Bill Bruckner

“Leroy #2” by Bill Bruckner

“Paul” by Bill Bruckner

2020-2021 - Staff Writer

2021-2022 - Online-Editor-In-Chief

I joined C Magazine because I love journalism and design. My favorite part about this...

2021-2022 - Staff Writer

2022-2023 - Business Manager

I joined C mag because art has always been a big part of my life. I always loved looking through...

2021-2022 - Staff Writer

2022-2023 - Editor-In-Chief

I joined C mag because I saw it as a really cool way to learn more about the Paly community,...

![UNSUNG HEROES — Fred Korematsu, Karen Korematsu and Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga are awarded the Asian American Justice Medal to recognize their fight for justice following the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. In addition, scientists Shuji Nakamura, David Ho, Tsoo Wang, Mani Menon and Chih-Tang “Tom” Sah receive the Asian American Pioneer Award. "[As a scientist,] it is crucially important to be able to communicate your work and your discoveries to [not only] other scientists, but also to the general public," Ho said. Photo by Talia Boneh](https://cmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/useee-600x400.jpg)