As the staccato beat of traditional Serbian instruments builds to a crescendo, Paly junior Zoe Jovanović begins stepping in beat to a clapping rhythm that characterizes the Serbian spirit. Draped in elaborate gold jewelry and adorned with a dark red flower in her braids, Jovanović prepares for the next moment onstage. Using dance as a form of precise storytelling, Jovanović guides the audience through decades of history.

For Palo Alto High School dancers like Jovanović, dancing is more than a performance art. They dance to preserve century-old traditions, pass down pieces of cultural history, find pride in their heritage and connect with their ancestral homeland.

For Jovanović, Serbian folk dance is a collaborative and community-based way to connect to her identity. Each energy- infused performance invites the audience to participate in the festivity and to cheer the dancers on.

“They [the audience] always love it,” Jovanović said. “The dance will start off not slow, but mellow. And by the end, we have these fast tempos, so everyone starts clapping.”

Jovanović began performing with Mladost Folklore, a Serbian Folk group, two years ago. Each Sunday, several Bay Area Serbian Orthodox Churches gather together to pass down traditional dance forms to youth in the community.

Serbian folk dance incorporates many aspects of Serbian culture from dance, jewelry and outfits. Serbian folk dances have been performed for centuries, often in a circle that symbolizes unity and community. Dancers hold hands or link arms, moving in synchronized steps to the beat of the music, following the ancient rhythms of their ancestors.

“In Serbia and the Balkans, every single village has their own traditional clothing,” Jovanović said. “But our group wears traditional clothing from central Serbia.”

Each traditional element has been passed down, connecting modern Serbians to the clothes that their ancestors wore.

“We have a white blouse and underskirt, a plaid skirt, a vest, which is called a jelek and a tight woven belt around our waist,” Jovanović said. “We do our hair in braids and wear silver and golden coins which jingle when we dance. Our shoes are called opanci, which are soft and great for dancing.”

“We have a white blouse and underskirt, a plaid skirt, a vest, which is called a jelek and a tight woven belt around our waist,” Jovanović said. “We do our hair in braids and wear silver and golden coins which jingle when we dance. Our shoes are called opanci, which are soft and great for dancing.”

Jovanović looks to Serbian dance as a way to honor her heritage and spread her traditions, especially with her family living in the United States. Folk dancing evolved into a way for Jovanović to interact and stay in touch with what can seem at times a distant country.

“[Dancing] is one of the ways that we can stay connected to our culture here in America,” Jovanović said. “Although I’m already connected to my culture, with [help from] my family, this is just another step, and it connects me to my ancestors and the history of my country.”

Paly senior Aditya Romfh has participated in Bharatanatyam, a South Indian classical dance, for 14 years. Bharatanatyam involves detailed poses arranged together to narrate a story accompanied by pulsing drum music and singing in the Carnatic style.

“[Bharatanatyam] is a combination of rhythmic steps which are joined together to form larger pieces,” Romfh said. “They can also include emotive pieces. You use your hands and different hand symbols combined with different facial expressions to convey either mythological stories or just stories in general.”

Even the smallest details, like the components of the costumes, hold significance and are carefully placed throughout dance pieces to emphasize and bring deeper meaning to each movement.

Even the smallest details, like the components of the costumes, hold significance and are carefully placed throughout dance pieces to emphasize and bring deeper meaning to each movement.

“There are a ton of components that go into your costume,” Romfh said. “Every part of jewelry and makeup has to do with either tradition, religion or a kind of aesthetic. On your feet, you wear bells. They’re meant to amplify the sound you make when you stamp your foot. There’s a fan that spreads in between your legs as you sit in this position called aramandi, and the folded fan expands and it amplifies that position.”

Deep religious and historical traditions are represented in the details of Bharatanatyam. As a two-thousand-year-old practice, it is weaved into the rich customs of Hindu culture and portrayed through dance. Even minor makeup and jewelry represent larger symbolism.

“Typically you’ll see a lot of dancers have dark, thick eyeliner, and that’s a cultural practice that was initially performed in temples,” Romfh said. “It’s to amplify the eyes and to enhance the emotions that you’re trying to emote with your face. You’ll often see a bindi, which is the red dot that you put on your forehead, and that symbolizes the third eye of one of the gods Shiva.”

The vast knowledge of cultural practices that Romfh has learned from dancing Bharatanatyam has allowed for a deeper understanding of Indian culture as a whole.

“Dance has given me a great pathway to learn about my culture and stay in touch [with it],” Romfh said. “There are a lot of [traditions] that come out in celebrations that you do at home, such as Diwali or Navaratri. But what was missing was a connection and a realization of all the mythological stories, ancient stories and the epics that I really enjoy learning.”

“Dance has given me a great pathway to learn about my culture and stay in touch [with it],” Romfh said. “There are a lot of [traditions] that come out in celebrations that you do at home, such as Diwali or Navaratri. But what was missing was a connection and a realization of all the mythological stories, ancient stories and the epics that I really enjoy learning.”

Dancing has fostered a valuable and intimate community between Romfh and his fellow dancers. Each dancer’s shared experience with the rigor of Bharatanatyam drives dancers like Romfh to keep performing.

“There’s not a single day that I’m not grateful to have this giant network of dancers that all support me,” Romfh said. “If I have a solo performance, they’re waiting on the side stage. I’ve known them for my entire life, so they’re all like older sisters.”

This community support is necessary for the grueling work needed to accomplish an Arangetram, where dancers ascend to a stage and demonstrate years of hard work. It represents the pinnacle of years of practicing dance and illustrates a deep story.

“I did a three-hour solo debut performance in August 2023 with live musicians on a professional stage,” Romfh said. “You perform eight pieces ranging from eight minutes, and there’s one giant piece that’s an hour long.”

The athleticism that comes with dancing is sometimes understated. Romfh has built up the endurance needed to perform each detailed pose for hours on end.

“They describe me as a very explosive and energetic, passionate dancer. It wasn’t always like that,” Romfh said. “The art form started being more of a devotional and religious art form, and now it has transitioned to have an athletic undertone to it.”

By providing a deeper grasp of his ancestry and culture, Romfh has transformed Bharatanatyam into an art form that has shaped his identity.

“It comes back to that religious and cultural component,” Romfh said. “Not that I think I would have missed out on it without dance, but somehow it just makes that connection to my culture stronger.

Melissa Dawn, an English teacher at Paly, is a member of a Ballroom dance group. Although she does not dance for cultural reasons, her dance group continuously uplifts her and is a fundamental part of her life.

“We have a community together, and its strength is in numbers,” Dawn said. “We’re all going to put on costumes, and we’re all going to go out and perform. It feeds our soul in a certain way that we don’t have to outgrow.”

Part of a dance community is the process of getting ready together. Intricate costuming and makeup are important parts of all styles of dance. They have historically been important in helping paint narratives with movement.

of dance. They have historically been important in helping paint narratives with movement.

“The reason why dancers talk about [costumes] is because dance is an aesthetic art,” Dawn said. “It’s all about your look. Makeup, hairstyle and costume are all parts of the appeal of performing for an audience; that’s part of what I love about dance.”

Ballroom dance has evolved greatly from its formal European roots, incorporating influences from around the globe. Even traditional American styles, such as swing dancing, have been shaped by Caribbean culture.

“A lot of American dance styles were brought from other places,” Dawn said. “They were made [American by] changing the beats, changing the tempos, rhythms and lyrics of the songs. But there’s also a fundamental change.”

Dance is an especially collaborative type of art, as it often involves large groups of people and webs of support. Whether they share a cultural identity or share the same passion and dedication, communities have undeniable impacts on dancers.

“All forms of dance are beautiful,” Dawn said. “It’s very important for both the dancer and the audience, there is a community there too – you do it for someone else, and you do it for yourself.”

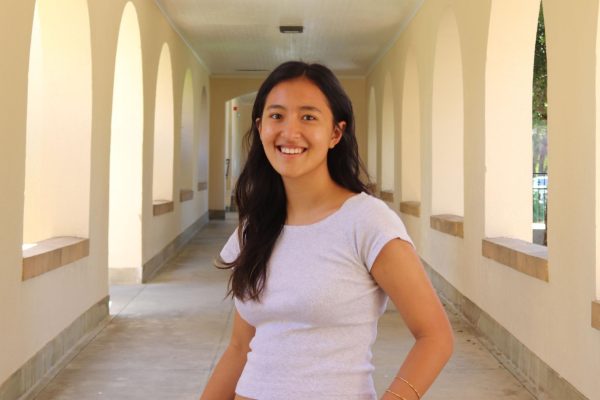

Paly junior Zoey Simpson, a Bharatanatyam dancer, dances to honor her family’s heritage, as her grandmother has been a key figure in her growth as a dancer.

“My grandmother has been dancing her whole life,” Simpson said. “Forty years ago she started the first Bharatanatyam school in the Bay Area as a way to preserve [Indian] culture in the US.”

Bay Area as a way to preserve [Indian] culture in the US.”

Outside the studio, her dance community is an integral part of her life. Living in America means her relationship with Indian culture is complex. Connecting with a group of people from the same background can enhance her sense of community and remind her of her cultural roots.

“I am only half Indian, so a lot of the time I feel distracted from my culture,” Simpson said. “But this helps me keep in touch with it, even with the community. I would go out and hang out with some of the girls [in my group] and eat the foods that their parents prepare.”

For Simpson, being mixed can come with presumptions, even within one’s own family. Older family members sometimes make judgments about her cultural identity.

“It [Bharatanatyam] has helped me get in touch with half of who I am, especially since a lot of those on one side of my family doesn’tlook too favorably upon mixed girls.” Simpson said.

Last year, she had her Arangetram. Her extended family’s mentality shifted as a result of this process. An Arangetram is consider

ed a rite of passage for South Indian dancers, similar to a coming-of-age ceremony or a

graduation.

“When they find out I’m dancing, they can sort of see me as an actual part of their family,” Simpson said. “Having an Arangetram is an achievement, a really big deal in India. It’s something to be proud of.”

Outside of the Indian community, stereotypes often prevent the work they put in from being fully acknowledged. Cultural dances are often misunderstood compared to styles that have become more popular in the US and Europe.

“[Some people] believe it is not as hard or as rigorous as other types of dance,” Simpson said. “It hits different muscles and in different ways; it’s not ballet or jazz, but it’s not less difficult. It’s just different. ”

Sometimes it can be a struggle to get other dancers to acknowledge the effort put into classical Indian dance. The dance community can sometimes make untrue judgments about the difficulty of cultural dance styles.

“A lot of other types of dancers don’t see it as a real dance form, which I think is a big part of the whole westernization thing,” Simpson said. “It’s just not seen as an authentic dance form in the same way some other [types] are.”

On the world stage, cultural dances can sometimes be overshadowed by dance styles usually performed at competitions. Many people are unfamiliar with the rigor and unique challenges that go into Bharatanatyam and cultural dance styles in general.

“Some of the Western dancers were upset when we got first place at a competition in Italy,” Simpson said. That was a little bit hurtful for us because we also came all the way to Italy and also prepared for months. We also danced.”

TraditioninMotion