“Boys will be boys.” “Man up.” “You’re fast—for a girl.”

While these phrases may seem like harmless remarks, they reveal underlying gender stereotypes that resonate both at Palo Alto High School and across the globe. While some may view sexism and discrimination as historical issues, derogatory remarks continue to impact society today, reinforcing cultural norms and shaping social expectations that affect individuals’ identities and interactions.

Recent shifts in social attitudes have begun to challenge these norms, prompting discussions on traditional views of gender roles. When navigating this evolving landscape, it’s crucial to address how stereotypes influence interactions and consider their impact on the broader understanding of gender.

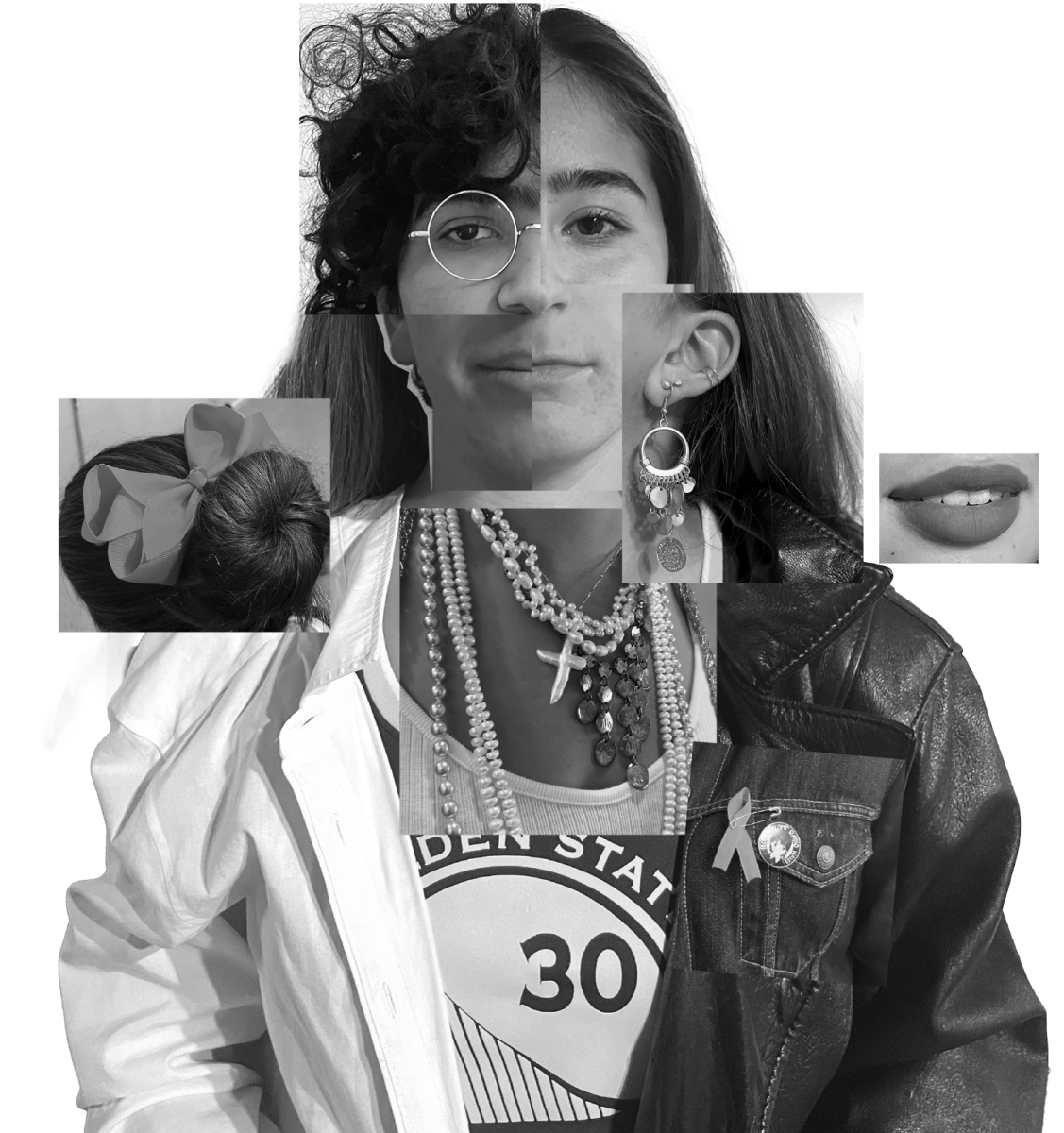

While progress has brought some positive changes, such as greater representation and legal protections, significant work remains in dismantling gender biases and raising awareness of the unique challenges faced by marginalized groups. Senior Salem Coyle has observed many of these interactions.

“The vast majority of sexism that I’ve seen on this campus has been unintentional — a product of how people were raised,” Coyle said.

Outright, blatant sexism is still prevalent in modern-day society, but teenagers today are more often targeted by seemingly harmless comments such as “man up” and “you scream like a girl.” These insults demonstrate historical gender stereotypes. Senior Riya Kini believes that there are specific, commonplace stereotypes against girls.

“The most prominent ones [stereotypes] are probably that girls like makeup, skincare and clothes and that it’s all we talk about,” Kini said. “People assume we don’t talk about meaningful things, and we just gossip and are materialistic.”

However, stereotypes are prominent for all genders. Junior Zeke Maples interprets what he believes to be common ones associated with men.

“The biggest stereotypes put on the male gender are that we always need to be stronger than others, that we’re not allowed to be emotionally vulnerable or that all men view women poorly,” Maples said. “Often, I’ve heard people say that men are less civilized than women.”

Different stereotypes and prejudices affect each individual differently. Henri Tajfel, a social psychologist, did a social identity theory in 1979 which explains how categorizing people into in-groups and out-groups leads to in-group favoritism and out-group discrimination. His research shows that even arbitrary groupings can reinforce societal divisions; Sophomore Leilani Chen continues this point, showing how this plays into discrimination.

“In reality, there isn’t much you can do,” Chen said. “It starts to become the territory of how do you fight the human nature to always otherize people.”

This is evident in sports, where gendered expectations shape how athletes are perceived and where achievements are often measured through a gendered lens, marginalizing the different groups.

In order to mitigate marginalization, it is important to recognize that sexism isn’t limited to school or work environments — it can happen anywhere. Justin, a freshman who chose to remain anonymous, elaborates on sexism taking place as a form of microaggressions, which are discriminatory statements or actions done in indirect, subtle or unintentional ways.

“It’s easy to forget about it [discrimination] and gloss over it, but

While there are many urgent global challenges, such as hunger, climate change and pollution, it’s important to acknowledge that sexism continues to be a persistent issue even if it may not be as visibly prominent as historical struggles. In a world filled with pressing political issues, sexism remains an undercurrent that requires attention.

“It’s something that can be so prevalent in our lives that after a while, you don’t notice the sexism implied,” Chen said.

Freshman Maryel Elizondo Salgado has experienced these microaggressions at Paly, which are present in sports and in our community.

Discrimination and prejudice have played a role in many students’ and working professional’s lives. Bennett Porter, Executive and Chief of Staff for Calm, a sleep and meditation app, shares how sexism impacted her work life when she first started working in 1995.

“I don’t think that anybody in the room did this [discrimination] consciously,” Porter said. “For example, they would ask the girl in the room to take notes rather than participate. It was just the way it was. I think it was very subconscious.”

Sexism can be learned anywhere—at home, on playgrounds, through social media or in movies.

“It’s a societal thing, and it starts in the household,” Justin said. “For example, I’ve often noticed that in a lot of households, boys are treated more leniently than girls. I think it really does start there and then it spreads to school.”

What actions can be done to counter sexism being learned in the household? More often than not, sexism is not a quality that parents intentionally instill in their children. Another anonymous junior, who will be referred to as Blake, believes there is a solution to this household issue.

“I would recommend parents assign household chores to all their kids at equal rates and treat them with the same level of respect and dignity,” Blake said.

In exploring the complexities of sexism today, it is crucial to recognize how the separation of boys and girls—and often the disregard of non-binary identities—can contribute to the issue of sexism and prejudice.

“When boys and girls are separated a lot and not given a lot of spaces to discuss stuff [sexism in their community], sexism tends to emerge,” Chen said.

To fairly look at sexism in a community, Blake believes it is vital to also look at the progress and pioneering taking place that help foster inclusivity on campus.

“What’s great is that there are a lot of empowering spaces at Paly,” Blake said. “The fact that there are male English teachers and female science teachers helps to change what people assume and fight common stereotypes.”

Gendered expectations leave little room for those who don’t fit traditional categories. Non-binary and gender non-conforming students can feel overlooked and alienated as society rarely accommodates their identities.

“I think a lot of transgender men who haven’t been able to medically transition yet tend to get lumped into just being ‘alt’ or ‘quirky females’” Coyle said. “That ends up being really damaging for us [transgender men].”

Gender biases don’t just exist in social interactions; they’re embedded in educational structures and experiences that influence how students see themselves and their futures.

According to a survey of 75 Paly students regarding sexism in Paly’s environment, many students believe gender bias is reflected in student participation in classes and the type of comments they receive. Ten percent of these students report that girls are often stereotyped as “neat” and “polite,” while another eleven percent report boys are more encouraged to take risks and be tough.

These stereotypes progress further down the road when discussions arise about what career paths are considered appropriate for each gender; different genders may be discouraged from pursuing a certain career.

“It seems it’s being pushed that guys are better at STEM things, like computers and engineering, which isn’t true,” Chen said. “I’ve seen so many different people excel in various classes, it seems unfair to classify a certain career to a specific gender.”

Overall, much progress has been made from where gender rights once were when Porter first started working and sexism was a daily thing. From the 1920s women’s suffrage movement which solidified women’s right to vote, to 1973 when abortion rights were granted to women, new social movements such as the “Lean In” and “#MeToo” have helped foster growth for women’s rights and established their place in the workplace.

The goal of the Lean In movement was to help women reach their ambitions and help companies increase inclusivity. The #MeToo movement helped survivors and victims of sexual violence find the confidence to speak out about their experience.

“Without the ‘Lean In’ movement, we [women] wouldn’t have found our voice to actually stand up for ourselves,” Porter said. “Because we started to demand more from ourselves, from our companies, from our spouses, it has paved the way to where we are now.”

Changes in policy, mindset and tradition have helped mitigate sexism in the workplace, the household and people’s lives.

However, changes in social culture such as an increase in social media use and online relationships fuel a kind of sexism where anonymous users have the freedom to comment online.

Social media has major effects on people’s ability to share sexist comments, contributing to the issue of microaggressions. Senior James Meehan highlights the impact of social media on our behavior.

“[Sexism is] definitely worse online because you don’t have to show your face so you can kind of say what you want hidden behind a screen,” Meehan said.

The more impersonal a social platform is, the more likely it is for comments to become harmful.

“I feel like Instagram is pretty bad with this [sexism],” Meehan said. “The comment section is very insensitive.”

Conversely, social media can also foster positive change by helping to challenge sexism and break down gender divisions.

“Social media has done some positive things for gender norms and stereotypes,” Kini said. “There are a lot of different people out there, like influencers, who are kind of atypical and don’t fit into stereotypes, so it shows a lot more inclusivity and new perspectives.”

Social media is a new part of social life; sexism wasn’t always so heavily portrayed through messages and media outlets.

According to the Guardian, after monitoring TikTok comments over a five day period, researchers have detected an increase in the level of sexist content from kids and teenagers. Kini expresses her impression of her peers’ perspective on sexism.

“It’s like they [teenagers] know they’re doing it, and they just think it’s funny,” said Kini

Jokes surrounding sexism are common in many social settings, not just online.

“I definitely would [hear sexist comments] in friend groups and groups of people—definitely jokes but nothing serious,” Meehan said.

Although people may brush these comments off as simply harmless jokes, they can still heavily affect people.

According to the World Health Organization, individuals who are persistently exposed to gender-based discrimination and stereotypes have a higher risk for mental health issues, including anxiety and depression.

About one in eight people live with a mental disorder, according to the World Health Organization, and the prevalence can be even higher among those who face discrimination based on gender.

How does society as a whole go about reducing and stopping this massive issue? Sophomore Julie Wang shares her solution to the issue.

“While it might be hard for the school to take action, it’s important that individually we stay aware of what we say to people, about their gender or how they are trying to display themselves and to try not to assume things,” Wang said.

Recognizing the effects of sexism—whether through microaggressions, stereotypes or systemic inequalities—is essential for fostering a culture of respect and understanding.

“I think we [Paly students] like to champion ourselves as very inclusive and past those sorts of gender norms but societal impacts still bleed over into our school, and we should, as a demographic, be more aware of that,” Coyle said.

To create a safer atmosphere, it is important to establish spaces where open dialogue can thrive, where individuals can raise awareness and confront the issue head on.

“Use that sexist comment to just have an honest conversation so that somebody can see your point of view,” Porter said. “If you want growth to happen and you want change, you’ve got to be open and you’ve got to have that conversation with someone.”