Eco-friendly! Farm fresh! Sustainable! Organic! Green! Bio! Recyclable! Carbon neutral!

These slogans are rampant throughout social media, online platforms and physical packages as companies attempt to brand themselves as supportive of environmental efforts. Most of these slogans are merely for clout and are often untrue, used for marketing or profit.

Known as greenwashing, this marketing tactic is becoming an increasingly prevalent issue. Brands try to appeal to their target audience by labeling them selves as more sustainable and environmentally friendly.

selves as more sustainable and environmentally friendly.

According to Robert Little, a Sustainability Strategy Lead at Google, greenwashing is a nebulous term with no compact definition and many complex layers.

“It [greenwashing] can be really intentional, like saying something that a product or service is made from 100% recycled content, and it’s just flat-out false,” Little said. “The spirit of greenwashing is trying to take advantage of a consumer’s desire to have a lower [environmental] impact … and using that as a competitive advantage when you’re selling a product.”

A company’s competitive edge via greenwashing stems from the increased awareness of the climate crisis and how everyday consumers can mitigate climate change by purchasing sustainable products. When it comes to the climate crisis, Aaron Nance, Paly senior and member of Palo Alto’s Youth Climate Advisory Board, thinks that companies take advantage of a consumer’s do-gooder mentality.

“This is happening because companies notice people are starting to care for the environment more,” Nance said. “So, they start greenwashing to gain customers who have this care for sustainable practices.”

Additionally, in many industries, companies that greenwash also have adverse effects on companies that are genuinely environmentally friendly. In the worst cases, companies that don’t greenwash can be accused of doing so.

“Greenwashing puts a bad name on companies that are truly environmentally friendly,” Nance said. “It promotes businesses to use this practice to keep prices cheap while gaining customers who usually buy sustainably sourced goods.”

Even outside of the corporate world, many younger world citizens feel the impact of greenwashing. Eco Club vice president and sophomore Avroh Shah believes some misconceptions are associated with greenwashing, and these biases could potentially harm progress in the fight against the underhanded tactic.

“One common misconception about greenwashing is that it is limited to the fashion industry, which is simply not true,” Shah said. “Greenwashing is very prevalent with industries across the board ranging from aviation to banking, especially as consumers increasingly seek environmentally-conscious habits.”

Even if a consumer is not consciously picking a product based on its ecological footprint, today’s increased awareness of the climate crisis will inevitably impact consumers. Google sustainability marketing manager Logan Chadde shares the belief that consumers may consciously choose to pick an eco-friendly product over an alternative if they believe they are doing good.

“If deciding between otherwise similar products, [a consumer] will choose the one that is perceived to be more sustainable,” Chadde said. “It’s seen as an easy way to ‘vote with your wallet’ or make an impact.”

Since many companies typically only focus on increasing their profit margins, there are not many incentives to slow the practice of greenwashing. Audrey Sullivan, Paly senior and president of the Business and Finance Club suggests that the concept of greenwashing is more complex than it initially appears, especially from an economic perspective.

“[Greenwashing] is essentially a negative externality that isn’t accounted for by business costs,” Sullivan said. “Firms have no incentive to do anything to offset the impact they have on the environment. The only potential incentive lies in consumer demand for more environmentally friendly products, which is what leads to greenwashing.”

Additionally, this decision to choose a more sustainable product is not always conscious; in fact, many consumers will unconsciously choose an eco-friendly product over one that’s not marketed as such.

“Most consumers are making a lot of calculations,” Little said. “And greenwashing is just one of the many different things that they’re weighing. It’s not as often intentional; it’s just one small aspect that may push somebody over the edge to buy a product.”

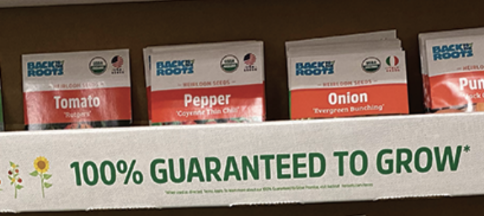

However, the conscious decisions of many consumers have become increasingly significant, drawing the attention of brands that seek to appeal to them through their packaging. Because brands are aware of consumers’ increased awareness while choosing sustainable-branded products, they will specifically package their products with this knowledge in hand to target consumers with this psychology in mind.

However, the conscious decisions of many consumers have become increasingly significant, drawing the attention of brands that seek to appeal to them through their packaging. Because brands are aware of consumers’ increased awareness while choosing sustainable-branded products, they will specifically package their products with this knowledge in hand to target consumers with this psychology in mind.

“I often see brands mark their packaging as ‘recyclable’ [instead of] actually making their package or product out of recycled materials,” Chadde said. “Being recyclable is great, of course, but that’s a pretty easy and cheap step and puts the onus on you.”

In some cases, the packaging will only be able to be recycled in a specific treatment plant, or, to recycle the product, the consumer will have to complete many extra steps.

“[Companies] claim that you can recycle [products],” Little said. “Of course, that’s true, but it has to be in a specialty program; it’s not in your curbside collection bin. Also, a thing that’s less than two inches is going to fall through the grates at a recycling facility. So, it is recyclable, but not in the way that consumer thinks about it.”

Similar to recyclable packaging, there are other ways to use more savory language to incentivize consumers to purchase a product.

“Promising to plant trees is another one [tactic] to be a little wary of,” Chadde said. “It’s not just the planting that’s important — you also need to ensure the tree stays alive and healthy for many years.”

Though some consumers are concerned about environmental issues, others simply do not mind that much. Senior Nathan Jiang buys based on price and not environmental friendliness, opting for more government regulation when it comes to enforcing rules.

“As a consumer, you just trust their [a brand’s] packaging or marketing,” Jiang said. “Nobody has time to do a deep check on every brand. It should be the government’s responsibility to ensure that brands are not greenwashing.”

In the European Union, there’s an Energy Label that mandates brands to include a grade on their product that’s regulated by the EU. Numerous factors determine this grade, and it’s given on a scale of A+ (maximum energy efficiency) to G (minimum energy efficiency). Any products that fall below the G category are banned. This incentivizes companies to actively pursue better sustainability. Additionally, this is an easy way for consumers to tell if a product is good for the environment, as the grade and its corresponding color are prominently displayed on the packaging.

“Environmental Product Energy Labeling, or Energy Label, is a very easy-to-interpret labeling system,” Little said. “It’s backed by the EU as well; it’s like a government label. I wish everybody had to have this [grade], and everybody was on the same scale. With this, as a consumer, I don’t have to do a ton of research to figure out if a product is good enough.”

In addition to supporting initiatives like labeling, Little believes governments have an important role to play in driving widespread change. This can be achieved by implementing policies that promote sustainability and setting clear standards.

“Governments can subsidize programs that encourage the reduction of waste and sustainable practices all along the supply chain, pass legislation that enforces compliance with environmental goals, and educate the public about environmental goals,” Little said.

Since the general public lacks insight into marketing decisions and business strategies, University of Chicago PhD student RJ Yang points out that a lack of awareness leads to poor consumer decisions when it comes to finding the most eco-friendly products.

“All consumers in today’s society who are buying stuff from these big companies are outsiders,” Yang said. “They have no idea what’s actually going on inside, or no control or any kind of way to even see what’s actually happening under the hood.”

In addition, though it is the brand’s responsibility to create honest marketing, many companies will sidestep ethical concerns of truthful messaging to promote business. Thus, as expected, the purchasing of less eco-friendly products in place of truly environmentally friendly ones can have an adverse effect on both the economy and the ecosystems around the world.

“Greenwashing makes people feel good that what they are buying is helpful … but if a company’s practices are actually harmful to the environment, then it can cause long-term damage,” Chadde said. “Wasteful companies will boast about using recycled materials or supporting environmental and climate nonprofits, making it hard to differentiate between eco-conscious companies trying to make a name for themselves and corporations that do a lot more harm than good.”

Because many consumers care about the environment, they will purchase greenwashed products, and the cycle continues, spurring many companies to continue greenwashing. Thus, companies that greenwash are profiting off of consumers and being rewarded for false branding.

“You might be putting money into the pockets of owners of companies who don’t care about the environment,” Yang said. “You’re just rewarding companies that are more willing to lie.”

However, the Internet is a powerful tool in the fight against greenwashing, and it plays a crucial role in exposing this tactic.

“When a business is exposed for something on the Internet, it is nearly impossible to sweep it under the rug,” Nance said. “Therefore, almost anyone who searches can find the information that they want, which is, in this case, if a brand is greenwashing or not.”

While governments should play a role in mitigating misleading environmental marketing, Chase comments that companies have an equally important responsibility,

“Companies should be transparent, avoid using misleading claims, set realistic goals, and track progress on achieving those goals,” Chadde said.

Though it can be challenging to navigate the rabbit hole of what is sustainable and what is not, there are many simple actions consumers can take to reduce accidental greenwashing, such as briefly looking over a list of misleading labels.

“It can be hard to figure all this out in a grocery store aisle or online product page, so you can always just focus on the brands you spend the most money on or buy most often,” Chadde said. “Perfectionism isn’t needed. Do what you can, especially for the most impactful purchases.”