To many, offshore powerboat racing is a high-octane sport that flirts with danger and demands extreme precision. Competitors fly across unpredictable waters at blistering speeds, navigating waves taller than cars and making split-second decisions that could mean victory — or disaster.

But to Wayne Vicker, it was more than just a sport.

It was a way of life.

Vicker never planned on becoming a champion. His journey began during the Vietnam War era, when he took a summer job at Mercury Marine.

“I got a summer job with Mercury,” Vicker said. “They saw talent I didn’t know I had.”

That talent led to a rapid rise. At just 20, Vicker was traveling across Europe with an international travel card, testing boats and earning a reputation as someone who could do it all.

But the beginning was far from smooth.

“My first race, someone was killed in the first hour,” Vicker said. “You’d think that would be enough. But it went from there.”

That kind of fearlessness defined his career. Even after close calls — like being electrocuted during a rescue or witnessing brutal crashes — he kept pushing forward.

“You just learn to overcome obstacles,” Vicker said. “I’m a water guy. I get it. I feel the water.”

What set Vicker apart wasn’t just his courage, but his technical instincts.

“I built a boat that was a little slower but better in rough water,” Vicker said. “If we finished every race, I said that we’d win a U.S. championship.”

Over the next several years, Vicker went on a tear. He captured two European championships, won the Bahamas Grand Prix and secured four consecutive U.S. national titles — a streak no racer had ever achieved before.

Vicker’s greatest strength was strategy. While other racers banked on speed, he built boats with endurance in mind. He also served as his own crew chief and throttleman—rare for a racer.

“We were a little slower than some boats, but if the ocean got rough, we had the advantage,” said Vicker.

That philosophy proved itself time and time again in brutal offshore courses, where most boats didn’t even finish.

In the Bahamas Grand Prix, the Blue Angels flew over the starting line in salute as the race began

“We got through the choppy stuff, and I couldn’t see another boat behind us,” Vicker said. “We had probably 10 helicopters above us. What a feeling.”

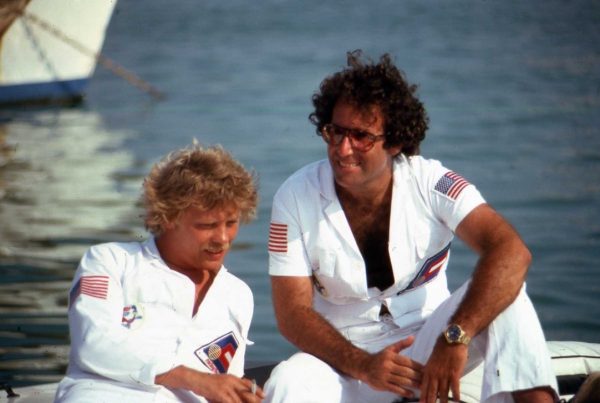

Over his 22-year career, Vicker raced across Spain, France, Australia and the Caribbean. He represented major international brands including Martini & Rossi and White Label Scotch, piloting their boats in front of thousands of spectators. For a time, he was the face of offshore racing in Europe, earning not just victories, but prestige.

“Everybody else looked like they were in a war, and you [Vicker] looked like you were doing the ballet,” a fellow racer during a race across the Gulf Stream said.

But like all careers at sea, Vicker’s time eventually reached its final lap. After a five-year contract racing in Europe fell through when a sponsor went to jail, Vicker quietly stepped away from the sport in 1980. He was in his 40s — national champion, global veteran and unsure of what would come next.

What followed was another chapter of reinvention. In Palo Alto, Vicker opened a coffee shop and designed his own espresso machine from scratch. With no background in business or food service, Vicker did what he had always done — he figured it out.

“If I can imagine something, I seem to have the knowing just to put it on the table with my hands,” Vicker said. “I learned about coffee beans, roasting, machinery, compressing the coffee — everything.”

To his grandson, Henry Harding, Vicker is more than a champion and a hard-working man — he’s a compass.

Even after retiring from racing, Vicker continued to reinvent himself. With no prior experience, he opened a coffee shop and built his own espresso machine from scratch, diving deep into everything from beans to mechanics. He chased excellence just like he had on the water.

“He taught me that it’s never too late to try something new and that dedication and curiosity can lead to success in unexpected ways,” said Harding.

Vicker’s story is more than a chronicle of daring races and broken records. It’s a reminder that greatness comes not just from success but from staying true to who you are, helping others along the way and never being afraid to chase the unknown.

![UNSUNG HEROES — Fred Korematsu, Karen Korematsu and Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga are awarded the Asian American Justice Medal to recognize their fight for justice following the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. In addition, scientists Shuji Nakamura, David Ho, Tsoo Wang, Mani Menon and Chih-Tang “Tom” Sah receive the Asian American Pioneer Award. "[As a scientist,] it is crucially important to be able to communicate your work and your discoveries to [not only] other scientists, but also to the general public," Ho said. Photo by Talia Boneh](https://cmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/useee-1200x800.jpg)