What if I told you that one of my most intense workouts didn’t happen on a soccer field or in a dance studio, but in a quiet room with a piano? Growing up, I juggled a variety of activities: Chinese school, English and math tutoring, swimming, soccer and piano. When people asked what I did outside of school, saying I played a sport always got a stronger reaction—“You must be so strong!” or “That’s so cool, my brother plays soccer too!” But when I mentioned piano, the response was usually a polite “That’s nice.” That contrast stuck with me. Sports were glorified, while the effort behind music—hours of practice, focus and discipline—seemed less visible and less valued in the world around me.

Behind the scenes, music felt so much harder than sports. Not only was it incredibly time-consuming, but it was also physically demanding: a workout no one saw.

When I started piano at age four, I had no idea how exhausting it could be. I thought it would be easy: just pressing keys and making music. I couldn’t have been more wrong. Every Sunday, I made the long trip to San Francisco for lessons. At home, familiar aches crept into my hands as they stretched to reach the right notes during my daily doses of Mozart or Beethoven.

Despite the challenges, I continued to play piano. The idea of bringing expression into the world and sharing it with others resonated with me. There was something deeply gratifying about transforming black notes on a page into sound. I loved that I could interpret the music in my own way, shaping it around my tastes rather than conforming to tradition. Over time, I developed a more aggressive, free-flowing style, full of punctuation and fire. I’ve been criticized for this by audience members and educators alike, but to me, it’s a reflection of who I am: a free spirit, unafraid to push boundaries.

My journey to the flute started on a whim. In fifth grade, when it came time to choose an instrument for the school band, I simply checked the top box on the form, which happened to be the flute. I thought I’d only play for a year, but I was wrong.

I looked forward to picking up the flute every day. Something about the cool metal against my skin, the delicate keys beneath my fingers, and the precise breath control it required made it feel special. Playing the flute while standing gave me a sense of freedom I never had at the piano. I could move, sway, and feel the music with my whole body, rather than being confined to sitting at a bench. That physical freedom opened a new path of self-expression. What started as a simple curiosity has since blossomed into a lifelong passion that continues to bring me joy.

As I kept playing the flute, unexpected doors began to open. I joined an orchestra, something that isn’t typically possible with piano since it’s not a standard orchestral instrument. Through orchestra, I made new friends and even began traveling the world to share my music.

One especially meaningful memory was the Golden State Youth Orchestra’s 2024 tour to France and Spain. I remember exploring unique street markets in Aix en Provence, visiting historic landmarks in Lyon, and seeing our concert posters displayed throughout the cities we visited. It was surreal to perform in packed halls where people genuinely wanted to hear us—we weren’t just playing music, we were part of something bigger.

I also grew closer to my fellow musicians, and those shared experiences became unforgettable. In Toulon, a famous port city, my friends and I snuck out of our hotel to visit the nearby port. We took photos under the night sky, laughing and enjoying the breeze: it was one of those small, perfect memories that stay with you for a while.

However, playing the flute came with its own physical challenges. Like piano, it’s physically demanding, but in an entirely different way. The flute is a transverse instrument, meaning it’s held horizontally to produce sound. Because rehearsals could often stretch from 90 minutes to three hours, with few breaks in between, over time, my posture began to suffer, and I started experiencing frequent aches in my neck, shoulders, arms, and back.

Holding up the instrument for long periods, maintaining precise breath control, and staying in proper posture all required strength and stamina I hadn’t anticipated back when I casually selected “flute” on that 5th-grade form. Visiting a chiropractor for the first time, one of the first things he commented on was how playing the flute affected my posture. After that first adjustment—the cracking felt so good—I realized just how much tension I’d been carrying from my playing.

Another challenge that comes with playing the flute is its high-pitched sound. Repeated exposure to these frequencies over time has noticeably affected my hearing. It’s even more intense with the piccolo, which flutists are often expected to play, especially in more professional settings like band and youth orchestra. The piccolo produces even higher frequencies, and without proper, professional-grade ear protection, the risk of hearing damage is significant. In my case, that damage has already started. In everyday conversations with my friends, I’ve noticed it’s become very difficult to hear them clearly. I often have to ask them to repeat themselves once, twice, sometimes three times just to fully understand what they’re saying.

Unfortunately, I’m not alone in this experience. Within the flute community, hearing loss is a known issue. One beloved member of the Bay Area teaching community, Isabelle Chapuis, who has been teaching for 33 years, suffers from severe tinnitus, and it’s heartbreaking to think that this condition has made it difficult for her to continue teaching.

This connection between the physical demands of playing and the toll it can take on the body goes even deeper. Flute playing depends on the precise use of small muscles. To produce a resonant tone, I rely on pressurized air, not volume, since too much air can overwhelm the flute. I engage my diaphragm to create a focused air column, similar to how singers project their voices. Tiny variations in airspeed or angle can drastically change the sound, so maintaining good tone takes serious energy, concentration and control.

But like sports, playing the flute can also be incredibly fun. Sometimes, it brings me into a calm, almost meditative state. There are moments when the music flows effortlessly, and I feel completely at peace; that’s when playing feels the most rewarding.

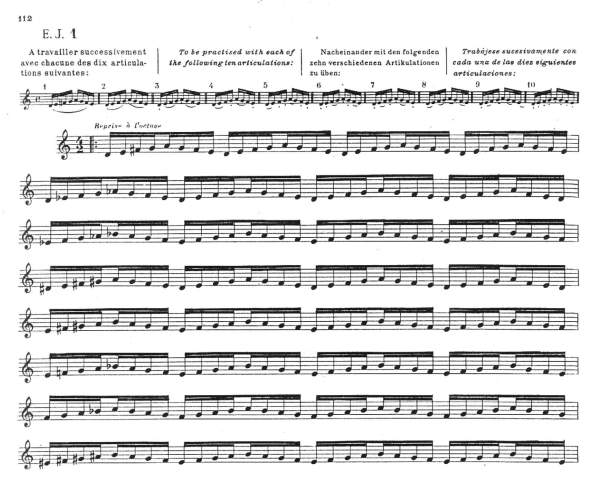

Similar to athletes, musicians must keep both their bodies and techniques in peak condition. For me, that means maintaining a consistent daily warm-up routine, practicing long tones, scales and tongue exercises every single day to stay in top form. These exercises are essential because they help build a strong technical foundation, which I rely on when tackling more difficult music. They also support the development of other crucial skills like tone control, articulation, and flexibility.

Playing in chamber groups or orchestras demands not only technical ability but also sharp listening skills and strong collaboration, much like team sports. Each musician must be attuned to the others, responding in real time to maintain cohesion and bring the music to life together.

The teamwork involved in music reminds me of playing soccer all those years ago. Just like in soccer, you have to be completely in sync with your teammates: strategizing, practicing together to perfect combo moves, and sometimes using unexpected plays to catch the other team off guard and increase your chances of scoring a goal.

In music, this dynamic appears when musicians in chamber groups or larger ensembles collaborate on interpretation, timing and phrasing. Everyone has to listen closely and adjust in real time. Interestingly, the most memorable performances often come from those who take creative risks and move beyond traditional interpretations, just like how clever, unconventional plays in soccer can lead to breakthrough moments on the field.

Solo performances, on the other hand, demand intense mental focus and resilience, much like athletes performing under pressure on the world’s biggest stages. There’s the mental preparation, the physical control, and, funnily enough, even Gatorade, a surprising commonality between musicians and athletes.

While it’s typically known as an electrolyte replenisher for sports players, I actually use it during high-stakes performances. Under pressure, I tend to get dry mouth, and Gatorade helps me stay hydrated and alert. It might seem like a small detail, but it allows me to stay focused, react quickly to the musicians around me, and remain fully present in the moment.

Though I no longer actively play sports, remnants of that world remain in my musical journey. Music has been incredibly fulfilling, not just as a form of beauty or emotional expression, but as a discipline that demands the same physical stamina, mental focus, and teamwork as any athletic pursuit. In its own way, music is a sport, and that’s part of what makes it so powerful.

If there’s one thing I hope readers take away, it’s this: the effort musicians put in, the hours, the physical toll, the emotional vulnerability, is just as real and just as worthy of admiration. I hope future generations of kids won’t have to feel like music is somehow less impressive or less important. We should see it not as a backup to something “more exciting,” but as a pursuit full of grit, creativity, and power.