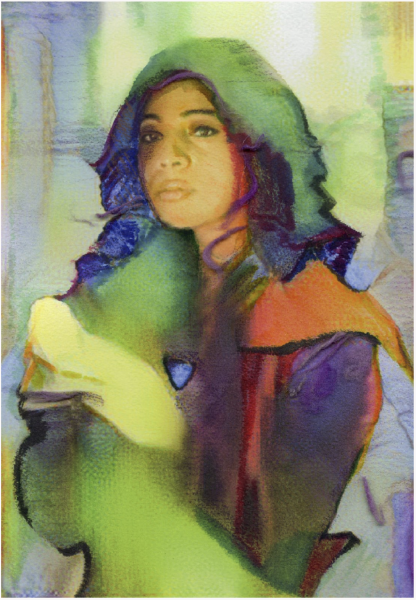

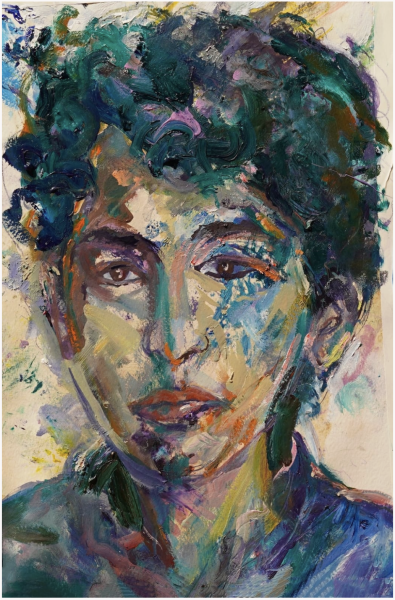

When I sat down to observe artist Pamela Davis Kivelson’s portraits and technique firsthand, I hadn’t expected the vibrant, almost surreal palette she would use to paint me. Tubes of indigo paint, spilling into yellowed linseed oil. Bright turquoise. A viscous Barbie pink.

Kivelson’s artistic process is messy, drippy, an abstract dance of color. Under indigo gloves, arcs of color converge to form a portrait, often more vivid and expressive than reality itself.

“Paint builds, accumulates and becomes physical,” Kivelson said. “It’s raw, it’s painterly properties—globby, messy, drippy, flowy, melty edges—there’s something about them that’s very human.”

For Kivelson, portraiture is more than a quick snapshot. It’s a conversation. An exchange. Over time, Kivelson gets to know her subjects. More than just a likeness on canvas, her portraits contain glimpses of the subject’s emotions that can be characterological.

“These [portraits] are a bit like dreams, memories and associations,” Kivelson said. “They contain what I know of the person, from what the person tells me. … Like when you’re writing a story, the characters have to tell you what they need, who they are and how they want to be described.”

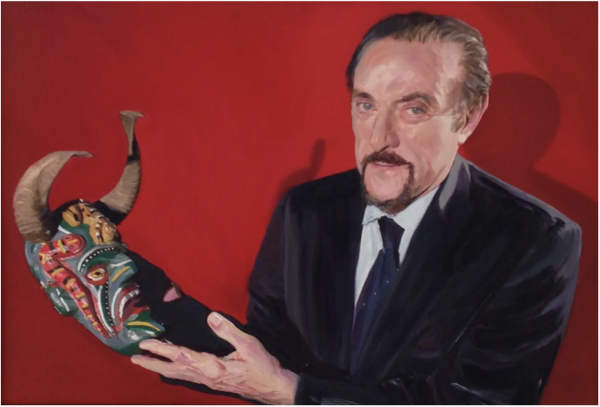

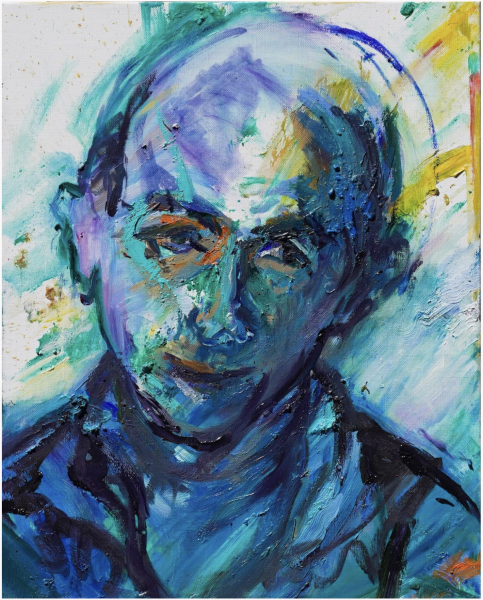

In one such portrait, as part of a series of seven commissions to paint some of the distinguished emeritus faculty from the Stanford Psychology department, Kivelson was asked to paint Social psychologist Philip Zimbardo, famous for the Stanford Prison Experiment and his contributions to the Heroic Imagination Project, a nonprofit research and education organization dedicated to training people to act in more heroic ways. At his request, Zimbardo’s portrait was influenced by his book “The Lucifer Effect.”

“When I painted his portrait, he asked for very specific things,” Kivelson said. “He wanted a bright red background. He wanted to look devilish, and he had some ideas in mind for what that would be. … He wanted me to paint him with a devil’s mask [and] he had a collection of devil masks from different cultures [to draw inspiration from].”

As part of the same commission, Kivelson was asked to paint gender and developmental psychologist Eleanor Maccoby. Maccoby was the first woman to chair the Department of Psychology at Stanford and revolutionized the study of sex differences in psychology by finding that many commonly held ‘gendered behaviors’ only notably emerged when children interacted in social groups with external pressures. Her research was foundational to the rise of feminism and women’s rights. Kivelson emphasizes that this is an example of why universities and research matter.

“Eleanor Maccoby was very interested in honoring women and women academics who were pioneers,” Kivelson said. “When I painted her, she really wanted me to paint her about to speak. She didn’t want her to be portrayed passively.”

Kivelson believes that portraiture is an art created alongside her subjects. The trust the subjects show in allowing her to paint them pushes her to not only portray an accurate likeness, but also ensure that the final piece resonates with their self-perceptions and desires.

“There’s an intimacy, because [the subject is] allowing you to really see themselves to some extent,” Kivelson said. “They’re being vulnerable. They’re giving you the gift of sitting and posing for you. … Someone’s honoring you with their time and letting you see them in this very exposed way.”

Stories like Maccoby’s and Zimbardo’s influence Kivelson’s portraiture philosophy.

“These kinds of stories really affected me and made me feel how incredibly important it is to portray the quality of a life lived over time and to honor them and their unique sensibility and global impact.” Kivelson said.

Currently, Kivelson is working on a series celebrating creative people, their thinking, humanity and uniqueness. Often, this means leaning into colors that are unexpected.

“I’m very interested in the idea that we are color, that there’s this underlayer you can almost [feel],” Kivelson said. “That you can take what’s happening in a particular exchange … and find the notes of color that … live under the surface of the contours of the face and what we’re used to.”

In recent years, Kivelson has also branched out to other mediums, such as videos and un-plays which are interactive extensions of her paintings.

Her most recent un-play which was recently performed at Oxford where she is artist in residence at the Physics department is entitled “Quantum Apparitions: The Physics of Loss.” The piece originated from her experience during the LA fires, where she lost her home and many of her artworks.

“I looked up at the giant, rolling, pink and turquoise Rococo clouds that didn’t look like any kind of clouds I’d ever seen before,” Kivelson said. “They were so over the top. I thought, ‘Oh, I should paint those. That’s amazing.’ I didn’t think, ‘danger, fire, I need to flee.’”

“Physics of Loss” attempts to grapple with reconstructing and recovering after the fire.

“You have to start over,” Kivelson said. “That’s all you can do. That really was the genesis for [the play]. This notion that you don’t have a choice, you can only go forward, you can’t go back. But in physics, information [like my portraits or my house] isn’t lost, it’s scrambled. Although it can’t be reassembled, it’s comforting to know that the information is still, in some sense, there.”

This is reflected in the way Kivelson constructs her artworks in the piece, allowing it to be more colorful, abstracted and loose.

“I’ve been particularly interested in the ephemerality of portraiture and life and how difficult things are in this moment, so having the drippiness or the portrait not be so controlled, having it feel almost like it’s being being erased while I’m doing it … [is] a way to respond to what’s [currently] going on,” Kivelson said.

This style—which Kivelson achieves by priming her canvases and papers with egg whites, coffee and salt—came about by experimenting with non-traditional materials in her art.

“There’s a lot of artists who play with the surface of their canvases,” Kivelson said. “You get really different layered and textural effects than you would get if you didn’t do it. You build up a lot of physical qualities on the surface. So before you even start the painting, the canvas has its own kind of life.”

Influenced by Italian mannerists such as Jacopo Pontormo, Agnolo Bronzino and Artemisia Gentileschi, their use of contrapposto—a twisting or torquing of the human figure—conveyed motion in a way that inspired Kivelson. She begins her portrait by scribbling on the canvas in order to find and commit to interior and exterior contours and shapes. By beginning with intuition, Kivelson is able to find a rhythm on the canvas.

“At some moment you have to let go, and you’re just in the moment performing and painting, letting your true feelings come through,” Kivelson said. “When art works, whether it’s singing or painting, it’s transient … but it stays with you.”

As Kivelson has matured as an artist, her practice has taken shape and developed a routine. Whether it’s painting color studies and works-in-progress, writing in her notebook, priming her canvas or reviewing conversations and dreams, Kivelson makes sure that, for a minimum of two hours a day, something creative is happening.

For Kivelson, being an artist isn’t a choice but a creative obligation.

“I die a little inside when I don’t [make art],” Kivelson said.

Kivelson’s beliefs and artistic practice has evolved and continued to evolve over her journey to become the best artist she can be. While her methods have changed, her focus has always been on the experiential, including representing human emotions in motion.

“Life for artists is painting one painting their whole life,” Kivelson said.

Kivelson’s portraits are on display at Stanford University in several locations: the Institute for Theoretical Physics (Varian Physics Building, 3rd floor), the Geballe Laboratory for Materials (3rd floor), and Jordan Hall. Her work can also be viewed on her website at https://www.pdkgallery.com/ and http://www.pkivelson.com/.

![UNSUNG HEROES — Fred Korematsu, Karen Korematsu and Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga are awarded the Asian American Justice Medal to recognize their fight for justice following the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. In addition, scientists Shuji Nakamura, David Ho, Tsoo Wang, Mani Menon and Chih-Tang “Tom” Sah receive the Asian American Pioneer Award. "[As a scientist,] it is crucially important to be able to communicate your work and your discoveries to [not only] other scientists, but also to the general public," Ho said. Photo by Talia Boneh](https://cmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/useee-1200x800.jpg)