It’s hard to imagine that when Emily Brontë wrote her novel “Wuthering Heights” in 1847, it would eventually be used — almost 131 years later — in a popular art rock song. Yet that’s exactly what happened in 1978, when Kate Bush’s rendition of “Wuthering Heights” became the first self-written song by a female artist to top the UK Singles Chart.

According to an interview she gave with BBC, Bush had been inspired to write the song after watching the tail end of a 1967 BBC adaptation of Brontë’s novel of the same name. Brontë’s “Wuthering Heights” tells of the destructive relationship between the main characters Catherine and Heathcliff. Bush’s high-pitched, keening vocals are directly inspired by the lingering presence of Catherine’s ghost later in the book, aimed to convey a more ethereal effect.

And Bush is not the only artist engaging with classical literature through their music.

Grace Slick’s “White Rabbit,” performed by the bands Jefferson Airplane and The Great Society, uses the cultural memory of Alice’s journey down the rabbit hole in ‘Alice in Wonderland’ to discuss the usage of psychedelic drugs in the 1960s, according to the Jefferson Airplane website.

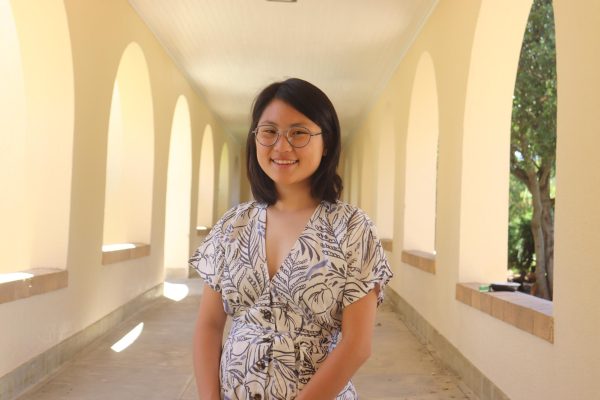

Singers like Taylor Swift and Lana Del Rey draw upon literature not only to enhance their themes but also as an aesthetic. In her album “Ultraviolence,” Del Rey references Anthony Burgess’ “A Clockwork Orange” to create a dystopian-like backdrop that enhances and better conveys her message — a bold strategy that freshman Youna Lee said allows artists to explore existing ideas in new ways.

“Musicians incorporate literature because they can usually [use it to] call back to themes that the literary piece or that author used,” Lee said. “It lets the artist explore new themes in their music by contrasting or building upon how another person explored a similar or a completely different theme.”

Similarly, junior and avid music fan Harry Bittinger highlights the idea of artists in conversation with each other. Even seemingly unrelated pieces of media can be largely influential to creatives working with a completely different medium.

Because of their popularity, these songs can encourage people who are otherwise unfamiliar with the references to read classic literature. For Bittinger, this opened doors to new interests and ideas.

“The Cure’s song ‘Killing an Arab’, which is inspired by the narrative of ‘The Stranger,’ introduced me to Albert Camus’ writing and the philosophy of the absurd,” Bittinger said.

For others who are already familiar with the referenced literature, beloved songs that incorporate these elements can drive further engagement with the texts.

“I already knew about [the books] before I listened to the songs, but after I listened to them, I researched a bit further, not only to discover what the artist meant with the references, but also because I was curious,” Lee said.

And while individual songs can act as a gateway to literary discovery for listeners, the conversation between music and literature extends beyond singular references. Artists sometimes dedicate entire albums to retelling classic stories, drawing from some of the most foundational tales in Western literary canon.

And while individual songs can act as a gateway to literary discovery for listeners, the conversation between music and literature extends beyond singular references. Artists sometimes dedicate entire albums to retelling classic stories, drawing from some of the most foundational tales in Western literary canon.

“There’s a lot of musicals and other longer pieces that are just literary references, like the musical “Epic: The Musical,”” Lee said. “The musical is just a big reference to “The Odyssey” by Homer. … It made me try to read daily.”

Literary giants like Shakespeare have also had a considerable impact on the field of music. His literary influence extends not only to thousands of books influenced by his stories but also to the various songs and musicians inspired by them. Phrases like “star-crossed lovers” and “green-eyed monster” have become common vernacular, often inspiring music like Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn’s “Star-Crossed Lovers” and Taylor Swift’s “Love Story.”

According to junior Kristella Ibuyan, songs such as “Our Lady of Sorrow” by My Chemical Romance embed tropes from “Romeo and Juliet.”

Paly music teacher Michael Najar also mentions that the Bible is often alluded to in many country, gospel and folk songs, sometimes in unexpected ways.

“There are clever uses of the Bible [in songs],” Najar said. “‘Solsbury Hill’ is a hidden story about Jesus rising from the dead or coming home, but you would never know that.”

However, literary references aren’t just limited to written text like the Bible or Shakespeare. Stories from folklore that reside within cultural memory can also become direct inspiration.

“There’s this song called Arari by Lucia … and it references the [Korean] folk tale of Arirang, which is about a young woman singing about how she doesn’t want her love to go away,” Lee said.

Beyond explicitly naming novels and characters, the dialogue between music and literature can be far more subtle. This is particularly effective when artists use the listener’s own knowledge of literary canon to intentionally subvert a familiar narrative, challenging preconceived notions.

“The songs that I like are the ones that play on [listener] expectations,” Najar said. “[For example], Jesus is a drinking buddy who is [narrating the story].”

Yet, not every reference carries the same weight.

“It’s really how well you tackle the literary reference and how much it actually builds upon your own themes,” Lee said. “You’re not just referencing some author to make yourself sound smarter, because it’s a fine line, but it’s definitely there.”

In many ways, these interpretations highlight the cyclical nature of art: literature inspires music, which prompts listener interpretation and responses. For artists, references can also be a source of personal exploration.

“Anyone who writes a song [with a literary reference] is … either trying to find inspiration, or has already been inspired,” Najar said. “Maybe they’ve heard about it, and they want to know more, and they’re questioning it.”

In the current day, questioning literature and offering new perspectives on outdated stories may not simply be interesting but an important part of modern discourse.

You’ve probably heard English teachers reference the idea of a singular story; that although many different stories exist, they are all facets of a singular tale: that of humanity continually retelling itself through different voices and seeking connection through shared experience.

In that sense, every reference becomes part of a larger narrative carrying forward themes that have resonated for centuries. When artists reinterpret literature, they are not only drawing on timeless narratives but retelling the stories that make us human.

“The idea of inherent unoriginality can ultimately be interpreted as a positive message,” Lee said. “Times are always changing, and although the work might not be completely “original”, per se, it’s new and it speaks the truth of an entirely new budding young generation of artists and people.”