2018-2019 - Staff Writer

2019-2020 - Managing Editor

2020-2021 - Editor-in-Chief

Hear more about me!

Most artwork focuses on interpreting and abstracting the beauty that is experienced in the familiar world around us. Recently, artistic concepts have been discovered within science and technology, revealing both the invisible and the undetectable by bringing forth the natural beauty of these hidden worlds.

March 5, 2019

Science continues to be a field of infinite uncertainty as individuals interchange between research ventures and artistic visions to capture nature’s exuding radiance. Whether it be through the visualizations of magnetic imaging resonance pattern scans (MRI) scans or photography through the microscope, the fluidity between science and art is on the rise. Intrigued and enlightened, the public both learns and admires a different perspective of science through these interactive exhibits and immersive images. As a result, the unseen beauty of the natural world is able to serve as an inspiration for many.

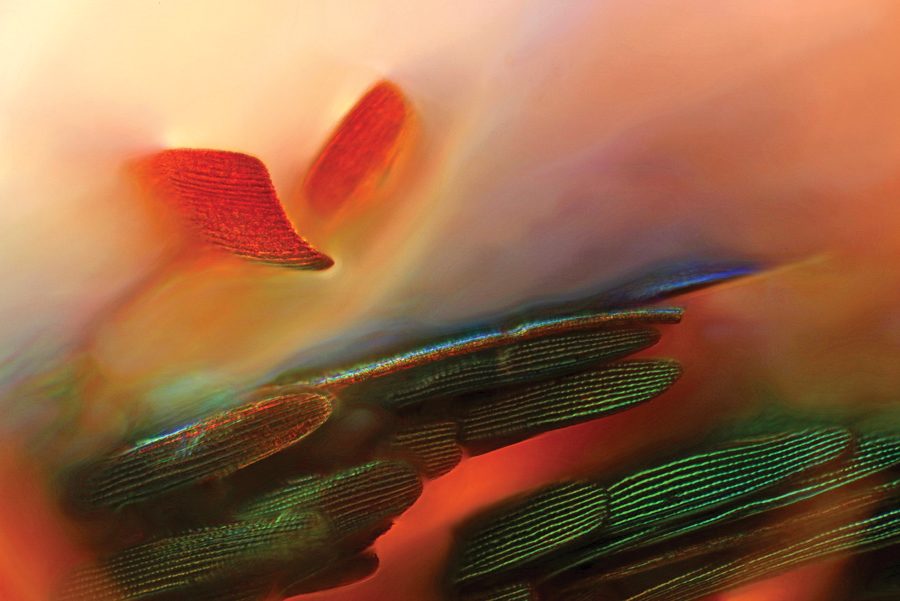

Air bubbles in polyvinyl alcohol by Marek Miś

Science continues to be a field of infinite uncertainty as individuals interchange between research ventures and artistic visions to capture nature’s exuding radiance. Whether it be through the visualizations of magnetic imaging resonance pattern scans (MRI) scans or photography through the microscope, the fluidity between science and art is on the rise. Intrigued and enlightened, the public both learns and admires a different perspective of science through these interactive exhibits and immersive images. As a result, the unseen beauty of the natural world is able to serve as an inspiration for many.

Walking into a black room, dust gets scuffed up from the floor, filling the air with earthy tones. The humming of chaotic insects can be heard overhead and the rapidly flashing LED monitors strike the creatures’ blue-tinted backs.

Known for the sensational diversity in his work, French artist Pierre Huyghe continues to exceed the limitations of the art world, no matter what form his art takes. Whether it be an interactive soundtrack, sculpture or monitor, the unique facets of his artwork create an unparalleled experience for the viewer. Inside his rendered conscious visual exhibit in London, called “UUmwelt,” over 10,000 living bluebottle flies circle the expanse of the gallery, perching on bright screens and a cool floor in addition to their airborne journey. Accompanying the winged creatures are strategically sanded walls and fluctuating humidity.

Huyghe frequently incorporates dramatically different mediums to compose an ecosystem that connects humans, animals and technological influence in his exhibitions. The flies provide a sense of unpredictability and never-ending motion as the sanded walls release a plethora of dust waiting to be moved about the gallery. Concurrently, the number of people present alters the temperature and humidity, even if ever so slightly. Although seemingly indifferent, Huyghe strives to emphasize the interrelations between the biotic and the abiotic, and thus, has light, temperature and humidity sensors that are constantly analyzing the exhibit’s conditions and changing the rate of the flashing monitors accordingly.

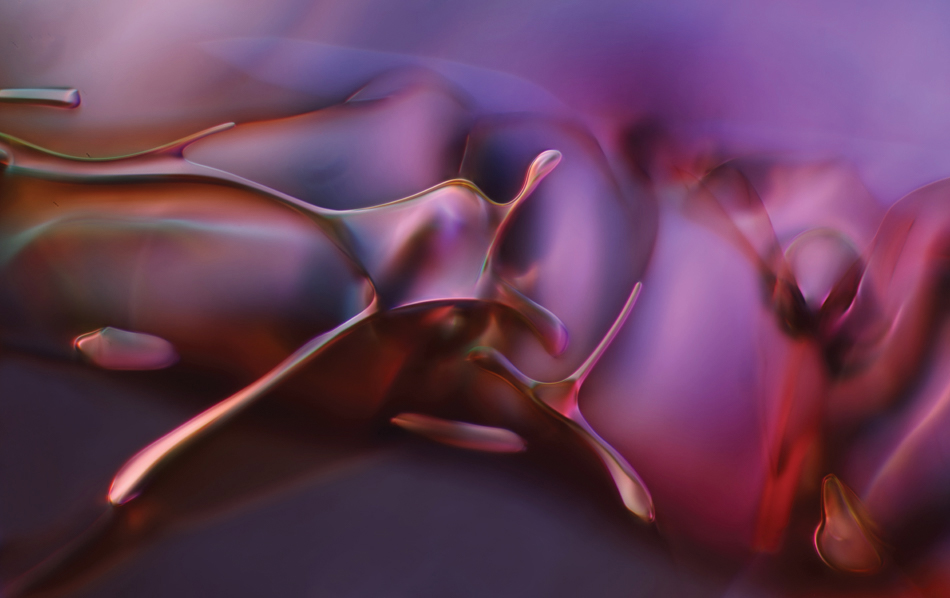

In order to regulate the speed at which each image produced by the MRI scan appears for, Huyghe embeds the collected light and humidity data through various algorithms. As a result, the embedded LED monitors can flicker the strange creations onto the screen surface up to a dozen times a second. Hence, insufficient time is left for the mind to analyze each individual frame, forcing the already oblique images to fade into nothing more but barely recognizable figures.

For a fleeting moment, the observer may be able to pick out a somewhat definite figure amongst the muddled explosion of color emitted by the monitors and projected onto the screen. Perhaps what you see is a brown beetle, while another spectator claims to have seen a brown bear. Alas, the chance to dwell upon one’s findings is ripped away as the image contorts into something unrecognizable, blending back into the dimensions of the frame once more.

Inevitably, countless moving parts and mechanics of the piece create room for discussion, as the perception of the work is entirely up to the viewer. When shown Huyghe’s unique exhibition, Alexander Nemerov, a Stanford art historian and professor, delves into a possible interpretation of the piece. “It creates a space wherein we can reflect, think, and in this case, on the increasing inability to think at all in the midst of whirring images that occur faster than we can comprehend them,” he said. “Accompanied by the restless disturbing buzz of flies and their implication of rot and death, the piece also suggests that we speed along, almost mindlessly, to the background hum of our own mortality.”

<

The process of developing these perplexing images begins with medical professionals taking MRI’s of Huyghe’s participants while they are shown a collection of images or described ideas. The recorded neural activity is then sent to Huyghe’s collaborator, Japanese neuroscientist, Yukiyasu Kamitani, who developed an artificial intelligence software that is able to convert the collected data into existent images through a deep neural network. This equipment draws from a preexisting bank of images and attempts to reconstruct and reproduce the participant’s conscious.

Kamitani’s machine-based learning technology was originally used in attempts to decode brain activity as people slept. With the combination of MRI scans and verbal reports, the decoding models produce a relatively accurate detection and representation of the imagery.

This particular union of science and art is relatively new, Huyghe being a pioneer of the style. To blur the line that separates the two fields, commonly perceived by many as polar opposites, is revolutionary in the name of the exact definition of art. Palo Alto High School art teacher Kate McKenzie is one of many who is intrigued by the endless possibilities the future of science and art beholds. “There are still so many unknowns in science and in art and when you put the two together it creates a vast playground waiting to be explored,” she said.

The world of science and technology surges forward and with it, a plethora of closeted ideas to bring to life and an entire universe to explore. Huyghe is one of the first, but as technology is used more frequently as an intermediate between science and art, society’s natural ability to create and discover can only flourish.

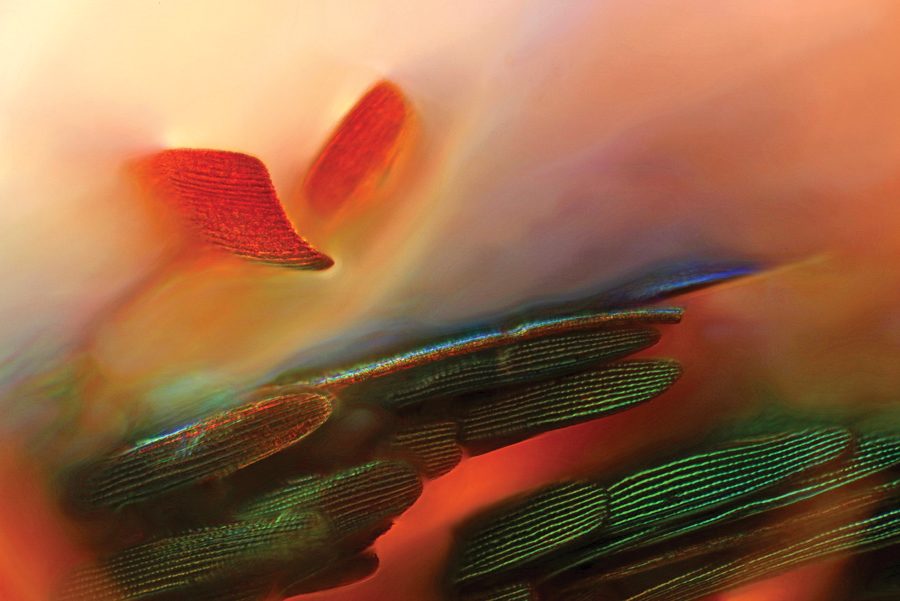

An amorphous burst of color flashes across an alien landscape. Vibrant shades splash about while distinct lines bring patterns into focus. This vitality of colors, patterns and strangely familiar designs is only observable through the lens of a microscope. There is more to nature than what meets the naked eye, and simply magnifying one’s perspective reveals an otherworldly beauty in butterfly wings, the shells of crustaceans or even just the bubbles in alcohol. With improving digital technology and an expanding interest in the microworld, scientists and artists alike are exploring the allure of the natural world through photomicrography, the practice of taking photos of samples from different crevices of nature through a microscope.

Before the rise of digital photography, photomicrography was considered a highly specialized skill that required years of training, and it was often only used in research contexts.

However, this quickly began to change as new technology developed to allow both professionals and hobbyists to take microscope photos. As avid supporters of photomicrography, Nikon Instruments contributed to this field by producing a multitude of different products, ranging from microscopes to software. To further promote the importance of the connection between art and science, Nikon established the Nikon International Small World Competition in 1975. The competition first began with the purpose to recognize beautiful images taken through microscopes and to showcase the work of photomicrographers from all around the world. Since then, winning photographs have been displayed in famous museums and on the covers of prestigious scientific journals.

Nikon’s Small World Competition is an international gathering of photomicrography enthusiasts. To Nikon Instruments’ communications manager Eric Flem, the competition also opens the doors to the public. “The expression of science through art helps provide a window for the public to see what the scientific community sees every day in their journey of discovery,” he said. “Much of scientific research is funded by the public, and a better broad understanding of things scientific is sure to have a positive effect.” By displaying the inner world of science through art, such as photomicrographs, science becomes more easily accessible and understandable for the public.

Photographer Marek Miś from Poland has devoted himself to taking micrographs since 2009. Facing difficulties in the 1980s with cumbersome technology and materials, Miś revived his passion when digital photography was made readily accessible. Miś has been a finalist in many competitions devoted to microphotography, and a wide variety of his photos have been featured on publication covers and in galleries.

“Photomicrography is a special type of photography because I can show what is completely invisible to most people,” Miś said. “It allows others, even for a moment, to enter a completely different world accessible only to people equipped with microscopes.”

Miś believes that anyone can appreciate the beauty of the natural world and should not feel limited by a lacking background or knowledge in science. “Photomicrography can amaze and at the same time delight with the beauty of nature,” Miś said. “You do not have to be a scientist to get inspiration from the micro world.” There are many instances where science is employed as a tool to craft art but in the case of photomicrography, art is used as a conduit to reveal the beauty within science.

In order to shift awareness from the macroworld to the microworld, photomicrographers use their artwork to reveal hidden portions of nature. “The natural world is so much more than what we see with our eyes,” Flem said. “The systems and series of events that have come to manifest what we are seeing are so complex. In the case of photomicrography, we simply employ tools that allow us to see what we physically cannot see otherwise.”

With photomicrography at the crossroads of science and art, this fast-growing genre of art has great potential. “Without science, there is no art and without art, there is no science,” Flem said. “Art and science are two sides of the same coin and by recognizing this, we only stand to gain in both realms.”

The casual viewer can observe the beauty in nature almost every day. From the elegance of math formulas to the magnificence of the tallest tree, millennia of human civilizations have always drawn from nature as a muse. As technology and scientific advances bridge the gap between the observable and the invisible, new ways to be amazed by the beauty of the natural world are constantly found.

2018-2019 - Staff Writer

2019-2020 - Managing Editor

2020-2021 - Editor-in-Chief

Hear more about me!