The American Dream

The incredible stories of immigrants reflecting the array of “American Dreams” existing in the U.S. today

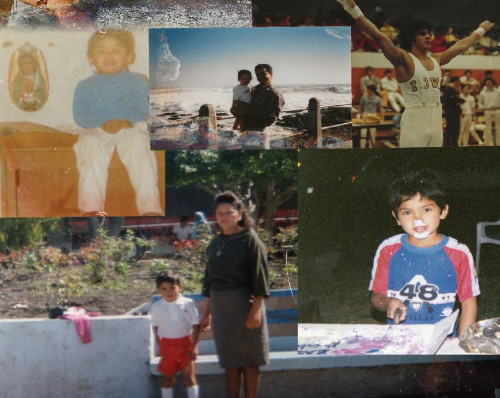

Pedro Rivas Lopez

Pedro Rivas Lopez, a current bay area resident, grew up with his parents, five sisters and three brothers in Cumuatillo—a small town in Michoacán, Mexico. People stood on the side of the dusty roads and sold mangoes and lemons to the cars that passed. Church bells rang and the cows roamed the land.

“The next thing you know, I’m getting a haircut, I’m getting new clothes, I’m getting jewelry, I’m learning this new language, and it’s all very sudden,” Rivas Lopez said. At age five, he was forced into a new identity; his mother kept telling him his name was now Robert and to forget his past as Pedro.

His next memory was waking up on a bus surrounded by his family and other immigrants. “As I looked to my left, I saw my mom’s hands clasped together, holding the rosary, and she was just praying and I just heard prayers bouncing off seats,” Rivas Lopez said. Continuing to look around the bus, Rivas Lopez remembers meeting the eyes of other confused children while their mothers prayed for their lives. “Then I heard that we were going to have to hide and have to run a lot,” Rivas Lopez said. The further the bus drove away from his home, the more worried he became.

Rivas Lopez suddenly woke up in the backseat of his aunt’s car with his cousin and six-year-old brother. His father was in the passenger seat. “I remember being afraid because I didn’t know where my mom was or where my other siblings were,” Rivas Lopez said.

As they approached the border, Rivas Lopez recounts seeing swarms of vicious dogs and men in uniform. “That’s when the documents came out,” Rivas Lopez said. “And that’s when everything started to make sense.” While they successfully crossed the border, Rivas Lopez still did not know where the rest of his family was.

He soon found that his mother and siblings were illegally crossing the border, through mountains and mud, on foot; they were forced to hide during their arduous journey. “My mom said that she was hiding under a ditch, and it was muddy and it was cold,” Rivas Lopez said. “There were rats lurking. Dogs were barking on chains and helicopters were hovering over them.” Despite the incredibly horrific trek, they managed to make it past the border.

Upon arriving in Fresno County, Rivas Lopez and his family of 11 lived in a run-down, abandoned office for a month that was full of spiders and snakes. He wondered why their family left their decent home in Mexico to reside in such living conditions.

After a month of living together in the one-roomed office, his family moved into a real house in the same town. That’s when Rivas Lopez and his siblings began going to school. “We were told that in America we were going to have an equal opportunity to go to school and to get a career going for ourselves,” Rivas Lopez said. Even at his young age, Rivas Lopez began to understand that his parents were putting their family through this dangerous journey full of sacrifice so he and his siblings could get a good education and become professionals in the workforce. His parents wanted them to have a life where they were financially stable and had ample opportunities.

Only a few months passed by, however, before Rivas Lopez’s dad pulled his older siblings out of school. “They needed to go to work to make money so that we could survive and actually live in America,” he said. One of his older brothers was determined to receive a good education, but during his sophomore year of high school, he was forced to drop out as the family needed more financial help.

His dad bought a grocery store in hopes of bringing their family to a place with more financial comfort, but even after that, his family was unable to make ends meet. Their idea of the American Dream, the one they had sacrificed so much for, began to diminish right in front of their eyes. They were becoming desperate. “So my dad started to sell drugs,” Rivas Lopez said. Instantly, his family was able to buy things that they not only needed but wanted. His dad didn’t tell Rivas Lopez, nor his siblings, about selling drugs, and they didn’t question the sudden influx of money as they assumed it was from the success of the grocery store.

While the money provided their family with more flexibility, the associated luxuries didn’t last for long. “My dad was caught, and then he was incarcerated,” Rivas Lopez said. For seven years, his dad served his sentence in a Texas federal prison and missed various important milestones throughout Rivas Lopez’s adolescence. “My dad didn’t see me graduate from my middle school graduation. My dad didn’t see me graduate from high school, nor did he see me in college,” he said. “But every graduation I dedicated to him.”

In 2007, Rivas Lopez’s father was deported back to Mexico following his release from prison. Soon after, his mother decided to move back to Mexico with him. Rivas Lopez remembered his mother saying “F**k the U.S.. That country has raped me and my family and I’m not going back.”

Rivas Lopez’s parents often call him, telling him to come back to Mexico. “So I ask them, ‘What about all the sacrifice that you made for me to come out here and find this American Dream?’ And my parents say, ‘Well we didn’t find it’,” he said.

Rivas Lopez often visits his family in Mexico but does not plan on moving back to Mexico anytime in the near future.

A large part of Rivas Lopez’s dream is to be financially comfortable. It’s about not having to worry about who is paying the rent or about how to pay for the next meal. He dreams of not having to worry about any of the things his parents were burdened with throughout his childhood.

Rivas Lopez is now living in East Palo Alto and is one of the new program directors at Dreamcatchers—a tutoring resource for low-income students in the Palo Alto Unified School District. He plans to continue working hard to live comfortably and attain American freedoms. “I think that America will give you freedom, but I think you have to work really hard for it.”

Anne and Mark Meyer

Born in 1923, Anne Meyer grew up in Vallendar, Germany, a small town in the district of Mayan-Koblenz. Meyer had a comfortable upbringing with her parents and sister and often recounted fond memories of her beloved childhood home. While she passed away in 2018 at the age of 95, her story is kept alive by her loving son, Mark Meyer, and the memoir she published in 2012.

At age 12, Meyer and her sister, raised in a jewish household, left their hometown and joined the Kindertransport to escape Nazi persecution. Throughout World War II, she hid in various homes as she struggled to escape and survive. Ultimately, she would become the only one of her immediate family to survive the Holocaust.

Meyer traveled from homes to churches and beyond to escape the same fate that the rest of her family tragically faced. In her memoir, Meyer recalls a time when she had an encounter with a Nazi soldier. As he attempted to converse with her, Meyer responded in fluent French instead of her native tongue. Only able to speak German, the soldier could not understand her and left.

In 1947, at age 24, Meyer learned of a first cousin who lived in San Francisco, California—she finally had a way to escape her past and start a new life full of hope and opportunity.

“She didn’t have anybody else, or anywhere else to go,” Mark said.

This family connection gave Meyer the means to leave Germany and start a new life in America. For Meyer, America meant opportunity and the chance for her to be a part of something bigger than the fear she faced in her home-country. “Her dream was safety, security and the ability to do whatever she couldn’t do when she was growing up,” Mark said.

That was her American Dream—to have the ability to do whatever she felt like doing, be free and not be limited by the government because of her religion.

Soon after arriving in America, Meyer realized that the next step in her journey would be to apply for citizenship so she could continue living a life of freedom. “It was a big deal for her to get her citizenship, she took all the classes and did all the studying she had to do to take the test to become a citizen,” Mark said.

Meyer considered gaining citizenship as one of her greatest accomplishments in life because she was now able to vote and hold an American passport. With all that America represents, she was finally able to call it home and accept everything it had to offer. Soon after, she met her husband, Joseph Meyer, and they had two kids. Meyer had successfully started a new life, one with security and safety.

Mark is a first-generation American and was born into a life of safety and freedom—one his parents did not have the privilege of growing up with. As a child, he did not have to worry about who he was, living in fear that he or his family might not see the end of each day.“When I was growing up, we didn’t know what it really meant to be first-generation Americans,” Mark said. “We didn’t know any better, we were just regular people.”

Throughout his adolescence, Mark always viewed his life as normal. While his parents spoke German to one another, nothing seemed out of the ordinary with his family. “[My parents] wanted us to speak English,” Mark said. “I did take German in junior high and high school, but there really was no pressure to not speak English.”

His parents had worked so hard to create the life he was living, but their complicated and extensive backstory didn’t mean that much to him until he was able to understand what it really meant to be an American.

“I appreciate what it means to be here far more when I am over 50 as opposed to when I was 15 or 20, and part of that is what’s going on today with politics, but I also had the benefit of living outside of the United States for a long time and traveling a lot,” Mark said. “You appreciate what you have.”

Over time, Mark has come to understand what his parents went through to come to America and he now appreciates the fact that he is living out their dream. As his life plays out, Mark understands the desires his parents hoped to fulfill in America.

“I think for my parents [the dream] was to have a family and a house,” Mark said. “For me, it is something similar, but I also think [the dream] is feeling like you are making a contribution.”

Kate Lee

Born in South Korea, Kate Lee’s journey to the United States began at Stanford University, 15 years before she would move there permanently. She first traveled to America with her husband as a foreign exchange student—studying as an undergraduate for one year while her husband got his Ph.D.—before returning home. Her life then continued in South Korea, starting a family with her husband, until two years ago when she decided it was time for a change.

“There were only four major reasons, three of them were primarily family reasons,” Lee said. “I didn’t get to see my husband, except just one day a week. After I became a mom, my little children didn’t get to see their daddy, except Sunday. And I thought that this is not worth it, you know, we don’t live to work.”

South Korea is notorious for a rigorous and exhausting work culture with employees expected to work long hours, which ultimately comes at the expense of time with family or friends. For Lee, family was more important than any job. “I wanted to raise my children with my husband,” she said.

Another concern for Lee was the intense expectations placed on children in South Korea. “There’s too much pressure on little children when they are not even elementary school students,” Lee said. “Asian parents were thinking that it’s important to train your children as soon as possible, as early as possible, which means that you start tutoring math when your child is six years old and I thought that was insane.” Although Silicon Valley is known as a hub for academic pressure in the United States, by Korean standards, the expectations are considered lenient.

Her children’s health and happiness were being threatened not only by the academic culture in South Korea, but also by the air quality. “The air quality in Korea was getting worse and worse because of China; when the wind blows from west to east, all of those polluted airs were coming to Korea,” Lee said. “When I was looking at my little children, I wanted them to have a good childhood and be able to play outside whenever they want to.”

Though her family has always been her first priority, Lee’s own professional career factored into the decision to move to the United States. She had been working for Google in Korea for eight years and decided that she needed to explore new opportunities.

“When you’re working in one thing, for many years, you have to broaden your horizons to expose yourself to a new set of opportunities or challenges,” she said. “Opportunities opened in the [Google] headquarter office, which is in Mountain View.”

After she received the position, she and her husband agreed to move their family across the world, uprooting their lives in South Korea. Their eyes were set on the future, with Lee’s heart and mind firmly grasped by the prospect of raising her children side-by-side with her husband.

Kiana Tavakoli

Packing up their entire lives, Kiana Tavakoli and her family left South Africa in search of a more prosperous and safe life in the United States when she was just eight years old. Leaving behind family members, friends and the beautiful city of Cape Town was difficult for her family of five, but they were willing to leave to start a better life.

Because of how young Tavakoli was during her move, she did not fully grasp what was occurring but was overwhelmed with emotion when it was time to leave. “On the day we left, we drove up a big hill to get to the airport,” she said. “I distinctly remember looking out the window while crying because I saw the ocean and the buildings that I would never see again.”

Leaving South Africa, Tavakoli’s parents inevitably sacrificed the lives they had built for themselves there. “I think it was hard to leave my childhood friends behind, but it was harder for my parents because they left behind all their businesses and hard work that they had built over the years,” Tavakoli said. “They left behind their friends that they’ve known for so many years and family.”

In South Africa, her parents owned three properties that were located next to each other: a hotel, their home and a block of apartments. Around these properties was a fence that acted as a boundary. “Because it was unsafe, I never walked or played on the streets alone, so I was really lucky to have this a huge space that was enclosed so I could still be creative and have fun in nature,” Tavakoli said. While this little piece of paradise within the fence may seem surreal to a little kid, her parents knew that as the children grew up, they would need to venture outside the safety of their property and have space to experience the world and grow—something that they could not easily or safely do in Cape Town.

Years before the Tavakoli family left Cape Town, they felt the desire to move from their unfriendly neighborhood but decided to wait longer in the hope of seeing a change in their country. “The economy was unstable, and the politics were unstable, so you never felt safe,” she said. When their country’s conditions failed to improve over time, they began their journey to the United States.

While it would be their first time going to the United States as a family, Tavakoli’s father had previously made the journey from Iran to America at 16 years old. “My dad’s American Dream was to come here and get a good education, get a job and become wealthy, but when he moved here, he had no money,” Tavakoli said.

Because he could not afford to pay for his education, he chose which college to attend based on the scholarship they could offer. Tavakoli’s dad ended up with a full scholarship and lived with his coach for the school’s gymnastics team, who provided him not only a place to stay but also meals every day.

After college, Tavakoli’s father moved to San Francisco to kickstart his aspiration of starting his own businesses. With hard work and dedication, he was able to achieve this dream. A few years later, he moved to South Africa, where he met his wife and proceeded to build businesses together and created a steady life for themselves in Cape Town.

Unfortunately, the unstable economy and lack of safety forced the Tavakoli family to make the 10,000 mile move to the United States in 2011. Tavakoli’s parents gave up everything they had in South Africa to provide their children with a better, safer future. “[My father] wanted us to start out with the resources that he didn’t have, and wanted us to have a good education,” Tavakoli said.

Because of the sacrifices made by her parents, Tavakoli has been given the opportunity to explore her passions and discover what she dreams of achieving one day.

“For a lot of people, the American Dream is just making money or having a family, which are good things, but I feel like, for me, there’s not one dream,” Tavakoli said. “I just want to be happy and be able to explore and experience a wide range of things.”

America is a country of freedom and opportunity, extending its invaluable privileges as a beacon of hope for those suffering elsewhere. Many only wish of such opportunities, but for some, this dream is willed into reality. Defined by perseverance and inspired by hope, the American Dream manifests itself in ways that make the greatest of feats appear within reach, waiting to be grasped.

2019-2020 - Staff Writer

2020-2021 - Managing Editor

Hear more about me!

2019-2020 - Staff Writer

2020-2021 - Managing Editor

I joined C Mag because of the fun spreads, creative designs, and interesting story topics!...

Katherine joined C Magazine because she was amazed by the creative designs as well as interesting text the magazine continuously presents. She love the...

2019-2020 - Staff Writer

2020-2021 - Creative Director

Hear more about me!