The Cartoon Revival

Cartoonists adapt to the digitizing world and overcome persistent criticism.

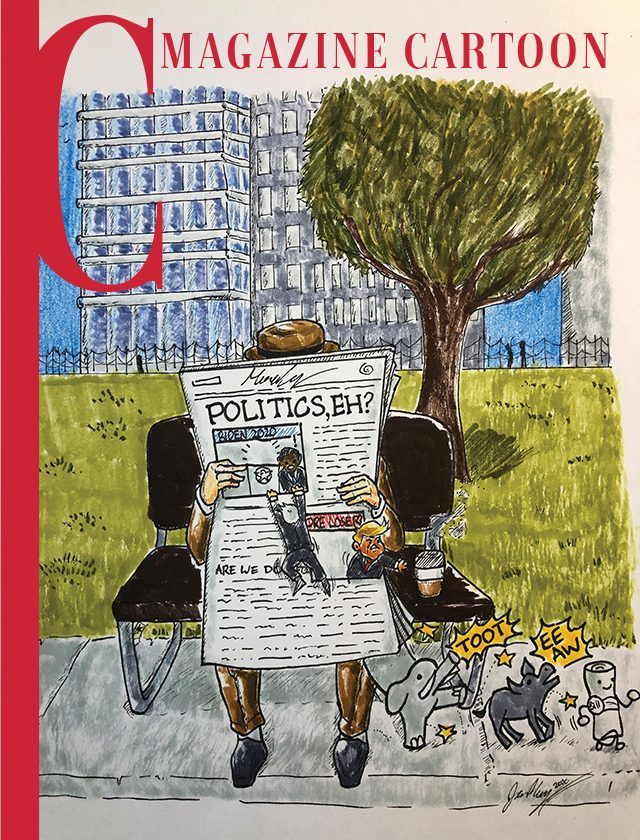

Your eyes scan the broadcasting news, picking apart the messaging and rhetoric of the politicians on screen. Your hands reach out for your stylus and iPad, exaggerating facial features, crafting speech bubbles, and writing thought-provoking titles. The most appealing topic you heard that day emerges as an image that effortlessly comments on our society and politics as a platform for constructive dialogue.

To create a meaningful piece, cartoonists implement caricature—the usage of distinguished characteristics to create a comic or grotesque effect—and satire as the stepping stones for political cartoons, providing light, comic relief from the stressful and bleak political affairs.

Though cartoons now hold great power in persuasion and entertainment, when political cartoons were still developing they were thought of very differently.

“They were considered vulgar, they were not treated as art, they were not displayed,” said Paly Comedy Literature teacher Joshua Hinrichs. “They were something you doodled in your notebook, but not something you showed to people.”

Political cartoons have evolved to become a platform for freedom of expression, but some artists still do not feel they get the amount of respect and recognition they deserve. Clay Jones, an American cartoonist, has experienced this struggle firsthand.

“I’ve been doing this for 30 years and I still feel like I’m struggling for recognition. But honestly, it took me seven years to get my first full-time job at a newspaper exclusively as a cartoonist,” Jones said.

Yet, political cartoons have been able to provide a new and unique perspective on journalism. They have the ability to convey meaningful information while also engaging the audience by allowing them to interpret the images themselves. Zoe Si, a freelancer cartoonist, acknowledges the power that cartoons have.

“I think cartoons are the best way to communicate a complex message, or an important cause, in a concise, easy-to-digest way,” Si said. “They can be dark, funny, and informative all at the same time, using a minimal amount of lines and sometimes no words.”

At the start of the technology era newspapers translated over to websites and TV programs, leaving political cartoons in the dust. While there may no longer be a place for political cartoonists in big-time newspapers, hundreds of people are still drawn to the political cartoon industry, and cartoonists have found an outlet online. According to the Herb Block Foundation, there are currently about 30 cartoonists working for a newspaper; a clear decline from the beginning of the 20th century, where 2,000 editorial cartoonists were employed.

“There is a quicker reaction from today’s audience because of social media,” Jones said. “It doesn’t take an audience an entire day to see my cartoon anymore. Now, it takes seconds.”

He has also noticed greater freedom online for cartoonists. “Some cartoonists are drawing more for a Facebook reaction than for actual news outlets,” Jones said. “A lot of stuff on social media won’t fly in a typical newspaper.”

With the new era of technology, Si has also found a lot more freedom and enjoyment in creating cartoons digitally. Instead of being tied down to draw about a certain topic, she can draw what excites her personally while still building an audience.

“There is much more permission to be silly with political cartoons, which I really like because I’m definitely more silly than serious,” Si said.

While these artists have all endured the modification in publishing and how they showcase their work, like any profession, they all face their own individual struggles. Whether it be the effect of censoring, opinions of the public, or even judgment from close family and friends, they put a lot at stake broadcasting their opinions in the public eye.

“[People] try to bomb my website, they troll my social media, they send me viruses in emails and they sign me up for racist newsletters,” Jones said. “They find photos of me and they put them on their hate pages for their people to recognize me and try to find out where my son lives so they can go after him.”

Something that never seems to change is the colossal amount of criticism they receive for drawing their opinions. But, Si does not let it affect her work, it makes her even more motivative to create stronger cartoons.

“I won’t ‘tone down’ a cartoon in order to make it more palatable for a certain publication. I have heard that selling inauthentic work is the best way to burn out, and I want to avoid that at all costs,” Si said.

Instead of being discouraged and fearful of the constant barrel of comments and criticism, political cartoonists build off that fuel and continue to use their power and influence to strengthen their message.

“If anything, I’ve felt compelled to speak out more strongly as I really believe in the cartoon’s power to unite people and make everyone feel less alone when things go sideways,” Si said. “It has definitely made me reflect on how lucky I am to live in a place where I can express myself freely through cartoons without fear of persecution.”

2018-2019 - Staff Writer

2019-2020 - Social Media Manager

2020-2021 - Creative Adviser

Hear more about me!