Reclaiming Ourselves

Students progression in their loss and love for their culture

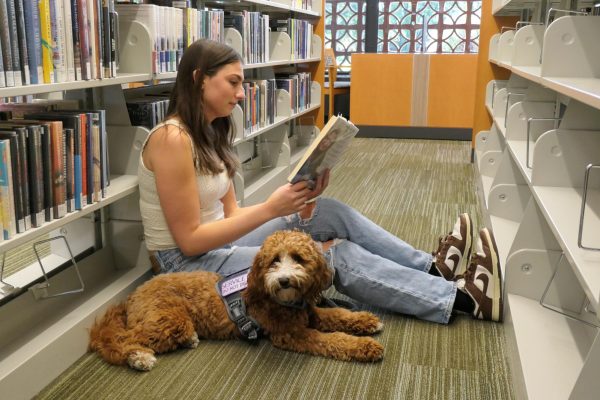

Junior Julie Chung walks through the halls of her International school. Anxious for what the first day will bring, she arrives at class early to make sure she is prepared for the new environment she is placed in.

Upon her arrival, Chung notices her classroom is filled with Korean students, contrasting with what she had anticipated before walking in. Looking around and hearing students have side conversations in Korean and adhering to Korean customs makes her feel out of place.

Chung spent the first semester of her junior year in Seoul, South Korea. Having lived in America her whole life, she was excited but scared to go back to the place her parents once called home.

In Korea, Chung faced some struggles—the international school that she attended there was drastically different from schools in America. Thus, she often felt like an outsider because she was not accustomed to Korean culture. More specifically, she was split between staying true to her roots while transitioning into a new environment.

“When I moved to Korea, I definitely realized how divided I was,” Chung said. “There were a lot of things that I didn’t expect.”

Despite her initial difficulties, Chung believes that the culture shock was necessary for her to transition from America to Korea.

“Honestly, I’m glad I got the shock, and I wouldn’t have prepared anything because it was very interesting to see the unexpected and the unknown,” Chung said. “I think that thrill was really nice for me because I got to adapt and learn [how] I can apply [the transition process to] real-life situations.”

Several students at Palo Alto High School share the same sentiment as Chung. Despite attending a diverse school with people from various backgrounds, many students experience a divide between themselves and their cultural lifestyle and traditions.

Junior Dinu Deshpande, a second-generation Indian American, is no stranger to this concept. A significant part of his own culture consists of celebrating holidays and keeping up with traditions.

“I have gotten the chance to celebrate a couple [Indian holidays], and obviously it’s a completely different feeling because the places I go to [in] India are upscale, with no foreign people,” Deshpande said. “It’s 99.9% Indians there, so everyone knows what’s going on.”

I had a phase where I was desperately trying to be more white. It’s so damaging because a part of me wants to be embracing my culture and the other part of me really wants to fit in because I live here.

— Celina Lee, freshman

Due to the fact that Deshpande has only been to India as a visitor, he never had the opportunity to immerse himself into traditional Indian customs.

“I definitely feel like there is a divide because I never experienced really living there,” Deshpande said. “Visiting is good, but it’s not close to living there.”

Similarly, senior Alondra Macias-Valencia, a second-generation Mexican American, does not know much about her own culture and customs.

“I’d like to say I’m somewhat in touch with my culture, but I’m really not,” Macias-Valencia said. “If anything, I like to eat my culture’s food, but I don’t really know the history.”

This process of drifting from one’s culture is common and experienced by many Paly students, but it also has a significant impact on the teachers as well. Teruko Kamikihara, a Japanese teacher, feels that she lost touch with her home country ever since moving to the U.S.

“About 20 [years ago], I lost contact because I did not go back to Japan,” Kamikihara said. “So most of the time, I didn’t have any information [about Japan] other than big news… I felt lonely.”

Furthermore, freshman Celina Lee believes that there are downsides to living in the United States when it comes to feeling connected to one’s culture.

“You’re not experiencing the same cultural benefits when you’re separated from [your culture]… it’s never going to be the same,” Lee said.

Lee, who is part Chinese, Taiwanese and Japanese, experienced some difficulties while trying to connect with all her different cultures. This struggle eventually led to Lee letting go of a part of her identity.

“I used to be very good at Japanese when I was younger, but I chose not to do it [later in life],” Lee said. “[There was] a decision where it was me choosing between Chinese or Japanese, and it never occurred to me to choose both, so I chose Chinese since my grandparents mostly spoke Chinese. I didn’t see why I should choose Japanese. ”

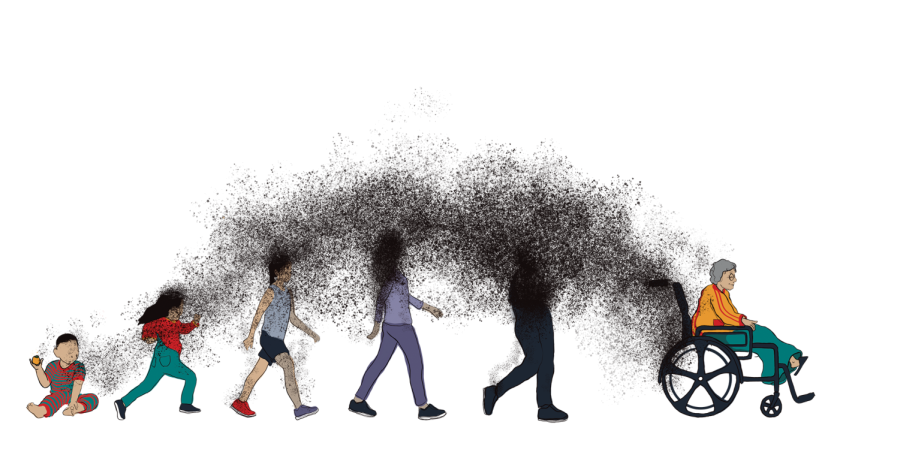

For a lot of Paly students, their desire to fit in cost them their love for their culture.

“I had a phase where I was desperately trying to be more white,” Lee said. “It’s so damaging because a part of me wants to be embracing my culture and the other part of me really wants to fit in because I live here, I’ve been raised here, and I have to go to school here.”

While the acceptance of one’s culture is heavily centered around an internal struggle, many times, people are forced to give up on their culture because of external forces.

There’s definitely more I wish I’d learned [about my culture], but I’m starting to learn that stuff now and getting more interested in itself.

— Dinu Deshpande, junior

Some attribute this struggle to the assimilation process of moving to America, where the cultural norms force an immigrant to lose a part of themselves in order to fit in. This loss also impacts future generations.

“I think America itself is a very one path type of thing,” Macias-Valencia said. “We’re not as progressive as everyone says that we are.”

As a result of this “one path” norm, many feel left out, which causes people to hide their identities to fit in.

“It’s definitely hard to not have that idea or try to embrace that [path],” Macias-Valencia said. “Especially when we’re surrounded by a bunch of white kids and white parents, you kind of feel like the black sheep.”

People living in America may also treat immigrants or second-generation people differently due to inherent biases they possess.

“There are some stereotypes surrounding culture that are almost looked down upon,” Lee said. “If you speak a different language, people here aren’t going to encourage you, if you have an accent, they’re going to look down on you [and] make you feel inferior. I’ve seen that with my grandparents and they’re…treated differently because they can’t speak the best and they’re not fluent. I think it’s really damaging to see that since I’m their granddaughter.”

In order to conform to a country where English is predominantly spoken, junior Johannah Seah also recounts that her parents began transitioning to speaking English due to the lack of resources that would help them continue speaking their native language.

“Language is a strengthening factor to culture, but I know it can be really hard in America because there isn’t a lot of access to Asian languages and translation, so it feels like English is the only thing [my parents] had,” Seah said.

However, not everyone thinks of themselves as whitewashed, or having completely lost touch with their culture because of the American assimilation process. Junior Alex Yan, a second-generation Cantonese American, believes that he has been using the resources readily available to him to stay connected to his culture.

“Honestly, I feel pretty lucky because the Bay Area has a lot of ways to access my culture, and there’s a lot of Asian people, so I don’t feel very whitewashed,” Yan said.

Deshpande agrees, as there are more resources now than in the past that can help people reconnect with their culture.

“I would say there’s not that much holding you back from being part of your culture or from learning,” Deshpande said. “Personally, I’ve never had real obstacles that have stopped me from learning about my culture and connecting more.”

While there are countless resources available to Deshpande, he has not taken advantage of them until recent years.

“There’s definitely more I wish I’d learned [about my culture], but I’m starting to learn that stuff now and getting more interested in itself,” Deshpande said.

Despite the struggle between external forces and internal feelings that cause a disconnect between people and their culture, there are still ways that students at Paly try to embrace their culture in the present.

Outside of just celebrating cultural holidays, the people that someone surrounds themselves with can significantly influence how they see their culture.

“I really value having Asian friends… [culture] is not just the holidays or the customs, but it is also about worldview,” Seah said. “I feel like another way of retaining my culture is by being with people who understand [my] experiences, and we also understand each other on a more personal level.”

Additionally, Seah visits several Asian stores to continue experiencing cultural foods.

“In the Bay Area, we have access to Chinese grocery stores and Chinese snacks, so I’m really happy about that,” Seah said.

People also use the internet to further their connections with their culture. For Kamikihara, who came to America when the internet was not as advanced yet, the internet is a great place for her to continue staying in touch with Japan.

Try to really understand what’s important in your culture and try to incorporate that into your day-to-day life and really feel okay with it. Don’t feel ashamed about it just because you don’t fit in.

— Alondra Macias-Valencia, senior

“We subscribed to live TV so I can see the news at the same time as people in Japan because of the live news center,” Kamikihara said. “What really helps is the internet. I can learn about music or how our culture is changing.”

The internet has also allowed people to contact others who experience their culture, such as family members who might not be in America.

“I always have my grandparents,” Lee said. “They just figured out how to use Zoom, and they Zoom us sometimes and teach us about different things. During holidays, they’re on the little iPad in front of us on the table. While it’s definitely great having them online, it’s definitely different from having them in-person.”

And even if a person feels divided with their culture, their culture is never truly lost. To further embrace their culture, people must put in work to strengthen their connections.

“[For example], just research what traditions [your culture] has,” Macias-Valencia said. “Do they have any rituals? Is there any sacred food in their culture? I think you definitely can [research] it.”

Just surrounding oneself with culture can create greater bonds, not only with their culture but the people as well.

“Sometimes just hearing stories is helpful because some cool stuff happens, and it’s very different to living in the US,” Deshpande said. “So I still like asking questions, hearing stories and trying to travel if that’s an option. [Those] are good ways to stay up to date and connected.”

Regardless of the level of connection a person feels with their culture, there are countless ways in which they can explore the connection that was once there. Even if one does not feel fully immersed in their culture, it is not something that people should be discouraged about or be embarrassed by.

“Try to really understand what’s important in your culture and try to incorporate that into your day-to-day life and really feel okay with it,” Macias-Valencia said. “Don’t feel ashamed about it just because you don’t fit in.’”

Art by Kellyn Scheel

Print Issue

Please click on the three vertical dots on the top right-hand corner, then select “Two page view.”

2021-2022 - Staff Writer

2022-2023 - Business Manager

I joined C mag because art has always been a big part of my life. I always loved looking through...

2021-2022 - Staff Writer

2022-2023 - Online Managing Editor

C Mag was really appealing to me because of its creativity and beautiful designs. I remember...