As November approaches and October comes to a close, the air is filled with gratitude and the warmth of family. For those who are part of diaspora groups, particularly second and third generation immigrants, connecting with family culture is a meaningful experience.

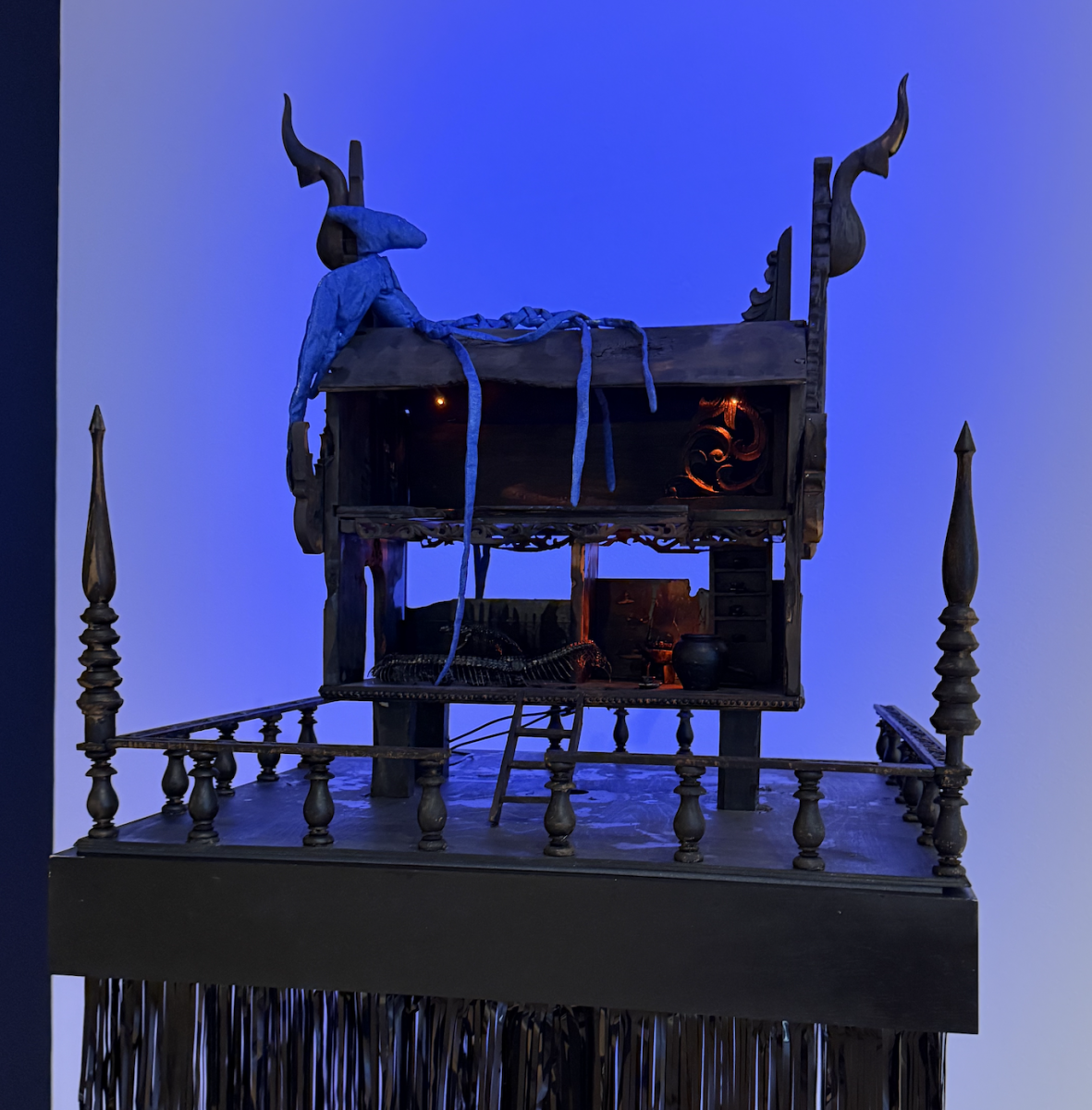

Cantor Arts Museum’s latest exhibit Spirit House, which runs from September 4 2024 to January 26 2025, explores the connections between the living and deceased, the cultural bonds that unite us, and the ghosts that stay and linger.

Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, associate curator of modern and contemporary art at the Cantor and co-director of the Asian American Art Initiative, has been working on the exhibit for two years. Spirit House is partially inspired by Alexander’s own experiences with sleep paralysis as part of the Thai diaspora.

“I am someone who has always believed in ghosts and hauntings,” Alexander said. “For as long as I can remember, I have suffered from sleep paralysis. (…) My mother and grandmother also have had this issue [sleep paralysis] throughout their life too, so it was a kind of strange family heirloom that I inherited.”

Despite the way Western sciences often pathologizes sleep paralysis, in Thailand, it is believed to be caused by a spirit called Phi Am. Spirit House seeks to explore new perspectives and open up new lines of thinking about such experiences.

“I wanted to open by talking about belief systems that think through the presence of another world, another dimension which are not necessarily grounded in what we might think of as empirical science,” Alexander said.

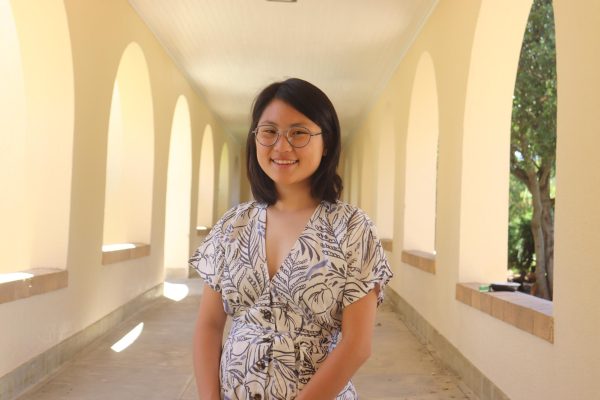

Spirit House is the first Cantor exhibit that is part of the Asian American Art Initiative, which launched in 2021 with the goal of advancing research and promoting accessible information on Asian American artists. Curatorial Assistant for the Asian American Art Initiative Kathryn Rose Cua comments on the ways artists in the exhibit draw from their experiences to create their artworks.

“So many of these artists are looking at the ways that global events have shaped their families, trajectories, their own livelihoods, even if it’s something that they haven’t experienced directly themselves,” Cua said. “It [these experiences] is an inheritance that they [the artists] carry with them generations past that initial event.”

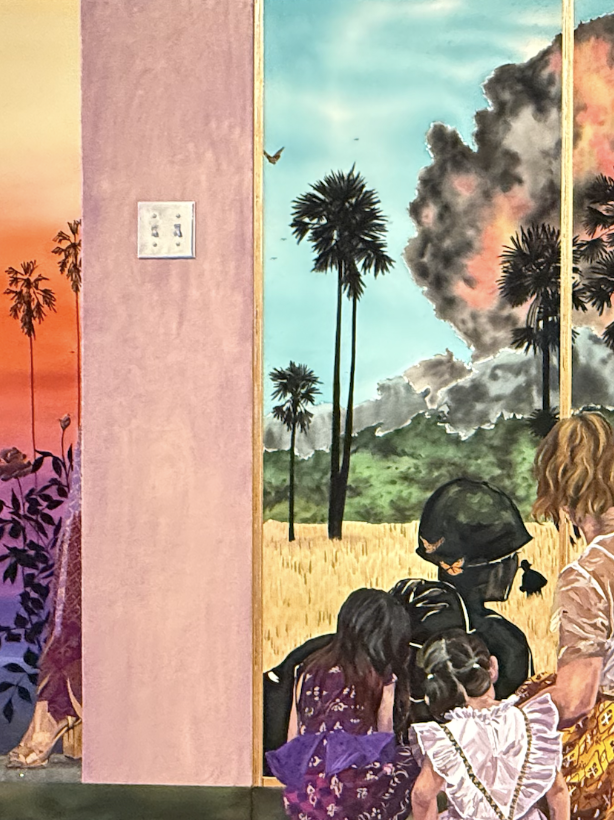

These reflections and experiences are evident in exhibit pieces such as Namita Paul’s Testimony, which dwells on her family’s experiences of forced migration during the India partition in 1947; Tidawhitney Lek’s Refuge, which references her father’s experiences following the rule of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia; and Kelly Akashi’s Life Forms which remembers her family’s incarceration at the Japanese American internment camps.

Despite not being an artist herself, Alexander considers the arts as a transcendent medium allowing her to bridge the gap between the different aspects of her identity and explore complexities of culture.

“For me, art and people who love art, and artists have become my third home,” Alexander said. “They have become the place where – even if I’mnever fully Thai and never fully American – I can hold those different parts of myself together with equal importance. The nice thing about art is that art is able to hold multiple truths at once, and also able to hold contradictions.”

For students in the US who are struggling to grasp their own identity, especially those who are second and third generation, art offers a bridge between different cultures they belong to.

“Living in the United States you can definitely feel othered,” Alexander said. “Especially depending on the density and diversity of the population where you live, it can be kind of isolating.”

Artist Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya honors this struggle in her piece What Remains (2024), spotlighting the labor, love, and compassion of the people working to preserve cultural heritage as well as the grief of those who feel disconnected from their ancestral roots.

“These artists are functioning as stewards of history and family narratives,” Alexander said. “So thinking about; what are the stories of our lives and our families that we’re going to continue to carry with us throughout generations? And do we have a certain responsibility to share and think about things like that.”

Cua shares her own experiences as a second generation Filipino immigrant.

“Even though I haven’t experienced displacement myself, this is something (…) that I have inherited, (…) something that my parents have experienced, and it’s something that has colored my existence,” Cua said. “That’s something many artists are reckoning with in the exhibition.”

Growing up in a predominantly white Chicago suburb, Cua went on to study art history and journalism in Missouri.

“My art history classes were void of the histories that I was seeking,” Cua said. “I think that this is true for a lot of people, where our histories [history classes] tend to be very Eurocentric.”

In graduate school, Cua took a 19th century class on Southeast Asia at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and was encouraged to write about a contemporary artist.

“I chose to write about a Filipino artist, and building a bibliography for that paper was really difficult,” Cua said. “I couldn’t find any literature, professors in my department couldn’t tell me scholars to look into. They had a really difficult time providing assistance for me (…) and that sort of lack was really disappointing, but it was also galvanizing for me. (…) That’s what made me realize that I wanted to study Asian American art history.”

As part of the Asian American Arts Initiative, Spirit House aims to provide context for the community, especially the younger generations. Arts professor and co-director of the Asian American Arts Initiative Marcy Kwan is already advancing the effort by teaching Stanford students about the works curated in the exhibit.

“[Marcy and I] both think that there is a huge gap in art historical scholarship and study [around Asian American arts],” Alexander said. “Being based in the Bay Area, where there’s such a high Asian American population and also a long history of Asian American presence, we thought that this was a great place to start the initiative.”

Spirit House is the first of many exhibitions yet to come. Spotlighting not just Asian American Arts, but the unique experiences of these artists.

Cua highlights Maia Cruz Palileo’s The Slow Course of Water, that interprets Mount Banahaw, a Philippine pilgrimage site, using a blend of written and photo references to honor the histories and lives of the Filipino people, overlooked under a western colonial lens.

“There are these sort of intangible things that don’t get talked about and inevitably shape our relationships with one another,” Cua said. “Something you can know to be true in your body even though it’s something that you’ve never studied. And I think this is, for me, what is really powerful about art.”

Although curated with the high number of Asian diaspora groups living in the Bay Area, the exhibition is not just for Asian audiences.

“Spirit house is very explicitly trying to generate new knowledge, especially about (…) artists who are having this kind of dialogue about their experiences,” Alexander said. “I wanted to talk about it in a way that honors the fact that these artists’ works are often informed by their experiences of belonging to an Asian diaspora. But that’s not all that the works are about. They [the works] are (…) also about larger topics that everybody can relate to. (…) I wanted to make something that I felt could reach everybody.”

Whether you’re seeking a reflection of your own experiences or looking for something new and meaningful, the exhibition offers something for everybody.

“What I have found most rewarding about this process [creating the exhibition] so far is just seeing all different types of people have really meaningful experiences with the artwork,” Cua said. “That is at the core of what I hope for, (…) regardless of their takeaway is, even if it’s just ‘I really love the colors.’”

![UNSUNG HEROES — Fred Korematsu, Karen Korematsu and Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga are awarded the Asian American Justice Medal to recognize their fight for justice following the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. In addition, scientists Shuji Nakamura, David Ho, Tsoo Wang, Mani Menon and Chih-Tang “Tom” Sah receive the Asian American Pioneer Award. "[As a scientist,] it is crucially important to be able to communicate your work and your discoveries to [not only] other scientists, but also to the general public," Ho said. Photo by Talia Boneh](https://cmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/useee-1200x800.jpg)

![Polynesian Club Performs at the Cultural Celebration Assembly

[Photo Courtesy of Savannah Earley]](https://cmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/PNG-image.jpeg)