Farm to Community

How the pandemic reinvented the way we buy groceries

It’s a Saturday afternoon when a buyer gets a “ping” on her cellphone. A text reminds her to retrieve her order of organic strawberries and radishes within the next few hours. After a trip to a local pickup station and back, she has everything she needs for tonight’s dinner.

Nicole Wang, a financial analyst at Stanford, knows this dance of preordering, memorizing pickup schedules and bringing home local produce like the back of her hand. Since Palo Alto went into lockdown last March, she’s been a frequent participant in the ongoing phenomenon of group buying.

“I saw friends [who participated in group buying] talk about restaurant meals or really fresh fish,” Wang said. “It made me very interested and I wanted to try.”

Known as “tuan gou” in China, group buying is a process where products are bought in bulk, resold to individuals and retrieved at a local level. Since this all occurs on the same day, the food arrives extremely fresh. Unlike traditional delivery services, there isn’t long distance shipping or door-to-door delivery, meaning high quality food can be shared with the community at a reduced price.

In fact, the practice of group buying first took off in the Bay Area as a form of contactless delivery—a way to purchase groceries without wandering through a crowded supermarket.

“There are less people in the middle, so I felt like there was less risk of the virus,” Wang said.

However, a new form of human contact was what initially attracted buyers like Wang. As the weeks went by, she bonded with her group organizers while placing orders and with other buyers while comparing items.

“There’s a relationship between the restaurants, supermarkets and each individual,” Wang said. “But ‘tuan gou’ changes the distribution chain, and the relationship changes from between restaurants and supermarkets to between individuals and individuals.”

The “beauty of tuan gou”—as group buying organizers have called it—isn’t limited to just buyers. It also benefits the farms that source the food.

Daisy and Abby Zhou are two sisters from Palo Alto who facilitate a “tuan gou” group. They first started getting involved before the pandemic to let their kids practice running a business, but as COVID-19 began shutting down restaurants and supermarkets, they realized what they were doing could help many people. [Editor’s note: Daisy and Abby Zhou’s quotes have been translated from Mandarin Chinese.]

“The farms were very nervous when the pandemic started and many of them came to us,” Abby Zhou said. “Supermarkets stopped receiving produce from them during the lockdown, so their fruits and vegetables would just rot in the ground. The problem was that everyone needed vegetables, but they were scared to go to the grocery store.”

That’s where people like Daisy and Abby Zhou come in.

“The farms aren’t able to do the detailed work [of distributing to individual customers],” Daisy Zhou said. With group buying, the process is smoother on both ends.

“People place their orders, and then we order from the farms,” Abby Zhou said. “After the farms send the food to us in boxes, we organize it by pound.”

Not even hours later, the food is already in the customer’s hands. But other than guaranteeing the freshness of their produce, the Zhous also make sure to sell only what tastes best.

“We try everything ourselves first,” Daisy Zhou said. “There are farms who want their crops to grow faster so they’ll use fertilizer. We don’t choose those.”

Jean-Pierre Mouloudj, Paly senior and founder of the nonprofit club Giving Fruits, has seen firsthand how Palo Alto has benefited from group buying.

“When people bought from us, we had a small margin that we could donate to good causes,” Mouloudj said. “At the time, I heard from several hospital workers that it was hard to get meals because they were either too big or too small. We were thinking we could donate to food trucks to make meals for them.”

Like Nicole Wang, Mouloudj has also noticed the social advantage to group buying.

“At the beginning of quarantine, we weren’t talking to anyone face to face,” Mouloudj said. “Because I was able to do Giving Fruits [throughout the school year], my people skills just skyrocketed.”

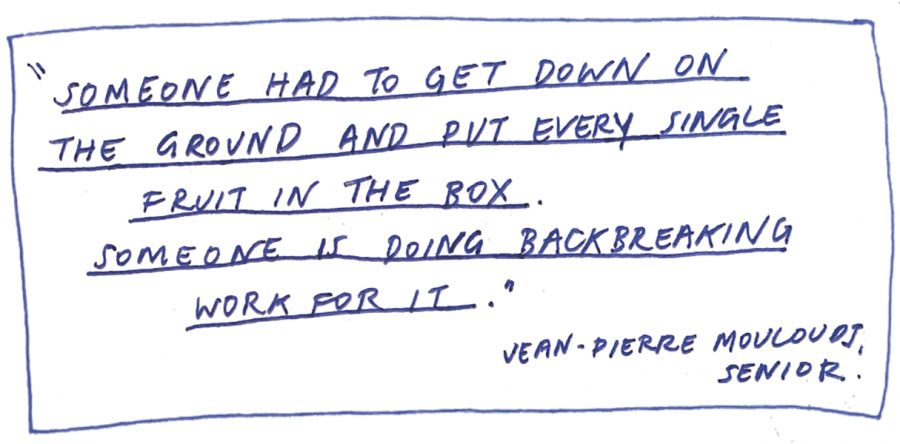

As he has to maintain constant communication with both farms and customers, Mouloudj has gained newfound appreciation for farmers who source the food.

“If you go to Safeway, all you see is a pile of apples,” Mouloudj said. “But when working with Giving Fruits, you can see the boxes are a little bit dirty, and you know that someone had to get down on the ground and put every single fruit in the box. Someone is doing backbreaking work for it.”

He also feels grateful for Palo Alto residents, who have been uniquely receptive to group buying.

“We tried integrating Giving Fruits in different cities, but it didn’t work,” Mouloudj said. “Palo Alto is the main reason this is working—people here are more willing to spend a little extra money to get something while having it benefit someone else.”

Following in the footsteps of group organizers and people like Mouloudj, others have taken group buying even further. Jenny Zhang is the CEO of smart locker company BoxNearby; by renting out lockers with integrated technology, BoxNearby allows customers to pick up their deliveries securely and contact-free. In order to keep up with the group buying craze, Zhang has started partnering with local farmers and businesses as well.

“COVID-19 shut us down and we found out that it was difficult for everyone to buy groceries, so we tried group buying,” Zhang said.

Although BoxNearby is still centered around their smart lockers, group buying has attracted a new wave of customers to the company.

“They said, ‘Oh, it’s so convenient. I don’t need to go to the store because everything is here,’” Zhang said. “‘Besides, everything is fresh.’”

Zhang’s operation is also simpler than other food delivery services, which hire drivers to deliver home by home. But while group buying is a better option for some (those living in apartments, for example), it asks customers to drive to pick up groceries, which can pose a challenge for some.

“One customer told us, ‘I have three small kids, I cannot come out to pick things up,’” Zhang said.

For Zhang, that only means expanding her company to meet the needs of more people—advancing neighborhood delivery, incorporating sustainable boxes and improving BoxNearby’s website are a few ideas in the works. After more people are vaccinated, she hopes to implement these changes and help group buying grow in the Bay Area.

“I go through my neighborhood and I talk to [people],” Zhang said. “Meanwhile, they’re getting yummy things and everyone is smiling. It makes your whole community come together.”

2020-2021 - Staff Writer

2021-2022 - Digital Design Editor

2022-2023 - Creative Advisor

I joined C-Mag because of our amazing page designs and...

2019-2020 - Staff Writer

2020-2021 - Business Manager

Hear more about me!