언니, اختي الكبيرا, 姐姐, Deirfiúr óg, Older sister

The various experiences of eldest immigrant daughters and how they have shaped their identities.

Reya Hadaya

I am the eldest daughter of a Hawai’i-born European and Japanese mother and a Lebanese-Syrian immigrant father. Within my parents’ cultures, emphasis is placed on the community rather than the individual. My upbringing was filled with sentiments of collectivism which have nurtured a sense of servitude within me. My parents pass down many of these lessons at the dinner table, a place where we engage in dialectic discussion about the state of our lives and their connections to our past.

However, my internalization of my parents’ values, along with women’s gender norms, have also led me to feel obligated to put forth my family’s needs before my own. Like many eldest daughters of immigrants, the expectation to bear the weight of significant familial responsibilities from a young age chipped away at my well-being. Up until very recently, my role in my household consisted of carrying parental weight that my parents could not, mediating complex familial conflicts, and being the primary source of emotional support for my younger sisters. This deprioritization of my own needs put me in a position in which I had to desensitize to my hardships and mature too quickly, creating an emotional distance between my parents and I.

I grew up without having to flee war or navigate poverty, a privilege that was not afforded to my parents as children. Although I understood that the severity of one’s hardships is relative to their life experiences, I felt immense pressure to face my circumstances without complaint or objection and to prove my parents’ plights as worthwhile. However, as I navigated the bounds between my cultural identity and personal values, I developed my own beliefs about my autonomy, and my sense of self began to grow independently of the person my parents wanted me to be.

In all my family’s disagreement and disconnect, I seem to return to the dinner table to revive our continual effort to understand each other and to move towards a deeper compromise. As I have come to understand that my parents’ expectations of me were based on our family’s best interest, much of my guilt and resentment evolved into forgiveness of myself for not fulfilling their standards and forgiveness of them for raising me in the way they knew best. I now understand that my upbringing as the eldest daughter has taught me the invaluable lesson of self-discipline, and I feel that my energy was not expelled but manifested through a growing clarity of my sense of self.

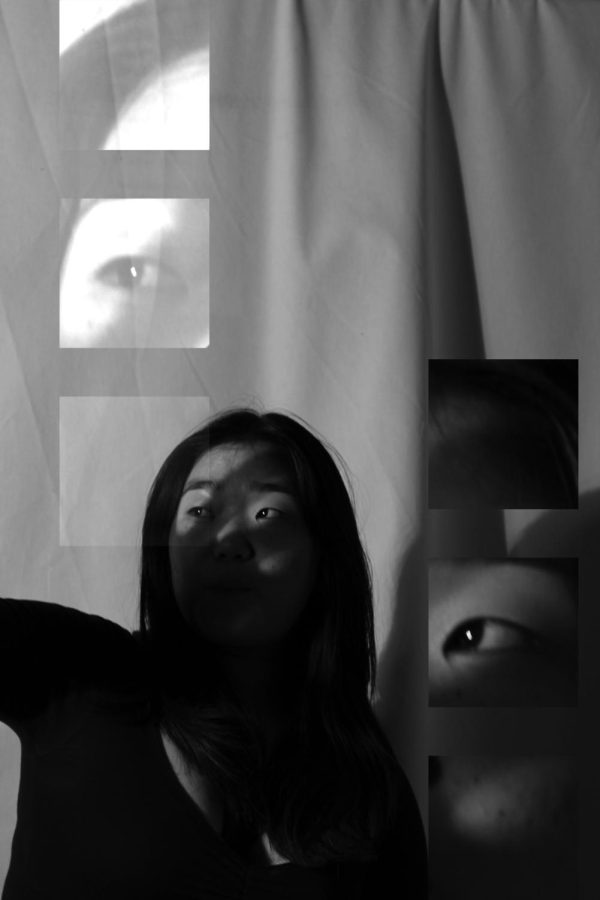

Eunchae Hong

Growing up as the eldest immigrant daughter, I never had any of the burdens that one in my position usually carries. My parents made the effort to give me and my brother similar responsibilities so that all of the pressure was not on me.

As my parents were born and raised in South Korea, it is safe to say that they had a drastically different upbringing than I did. They grew up in an environment where they were expected to do things a certain way, and if they did not, they would be looked down upon.

While my parents have made a significant effort to relieve my childhood of pressures that they had to experience, I often found myself trying to live up to these expectations because I wanted my parents to be proud of me, like their parents were.

I would try to be the “picture perfect” immigrant daughter because I wanted my parents to have physical evidence of why they moved to the States and that their struggles were worth it.

I believe that I had more pressure than my younger brother because I was the firstborn, and in traditional Asian households, firstborns have the responsibility of upholding the family’s legacy. My father, the first-born of his family, left behind a successful legacy back home, which made my grandparents proud to call him his son: I felt like I needed to fulfill this duty as well.

I often noticed the ways that my brother and I were treated differently by our parents. I quickly learned how to do things on my own, and strived to be an independent person. Therefore, my parents often left me to do things on my own as I “liked doing things a certain way” and because “I would always figure it out”. Conversely, my brother often went to my parents if he needed help with anything, leading him to develop more dependent characteristics that are seen in younger children of immigrant families.

My parents raised me to be organized, compliant and strong. As an immigrant, these are qualities that help us be the best version of ourselves and be accepted in our society. I believe that I have possessed these qualities and that it has shaped me into the person that I am today.

However, I have also learned how to branch out and become a version of myself that does not fit into the standard of the permissive and compliant immigrant. Through my own experiences, I have learned to be confident, outspoken and all of the characteristics that would not be commonly associated with immigrants.

Overall, the pressure of being the eldest immigrant daughter has taught me many things, and I would not take back these experiences as it has shaped me into the best version of myself today.

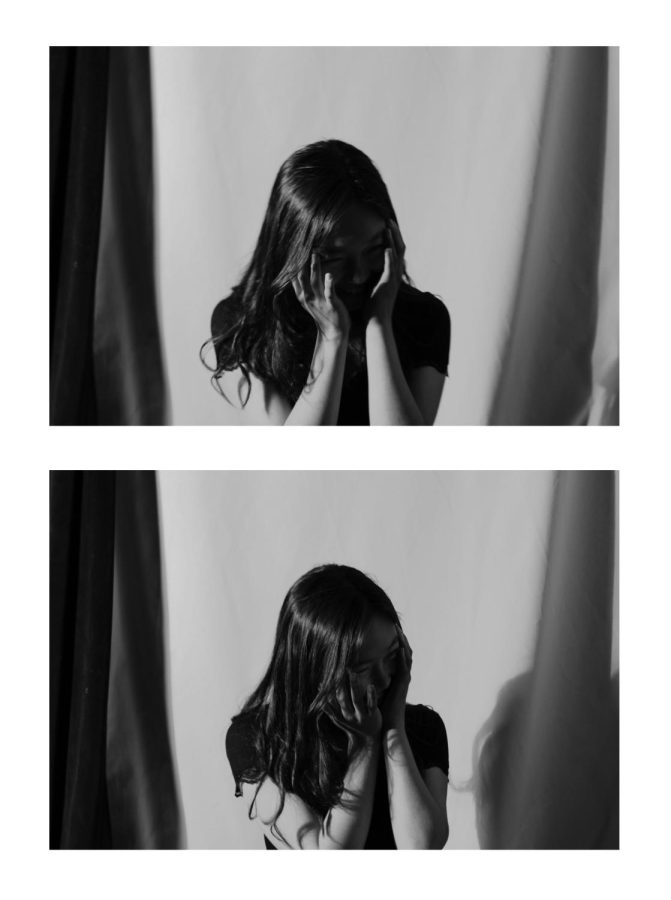

Eunice Cho

Wednesday. When Wednesday came around every week, I could feel the excitement bubbling up inside of me. Wednesdays were days when I went home with my mom after school, days when I could have playdates with my friends, days when I could take a break from the endless math and Korean worksheets pushed upon me by my dad.

Mondays, Tuesdays and Thursdays were reserved for DKC – Duveneck’s Kids Club. There, I would watch my friends and classmates enjoy the many games available to them as I struggled through page after page of addition, subtraction, multiplication, as well as the dreaded long division.

Fridays for me were the absolute worst. It wasn’t that I disliked my dad – he was funny, cheerful, encouraging – everything a father needs to be. But Fridays, and going home with my dad, meant seemingly endless lectures on math and science concepts that I dreaded.

Who would I have become without my dad’s worksheets? Maybe I would have turned out a bit more like my younger sister, who skated through elementary school without the same pressures I had. Maybe I would have turned out a bit more like my friends, who are able to prioritize having fun over their studies.

Actions such as these from my parents instilled a sense of responsibility in me. Even though I was never given the responsibility of taking care of my sister or put in charge of any chores in the house, there was always a constant burden to represent sensible characteristics. Small but mighty, this responsibility held me back from having too much fun whenever I went out and making the “wrong decisions”. It pulled me forward into spending countless hours studying for exams and writing essays, not because I wanted to, but because I felt that I had to.

I will never forget the last words my grandfather said to me, which were essentially, “Study hard and become an admirable person.” My experiences as the eldest immigrant daughter may not be very different from all other youth living in the pressure cooker that is the Bay Area. Still, the expectations from my family shaped my identity into what it is today, someone who embodies the admirable characteristics of a person driven towards success.

Evie Coulson

My immediate family immigrated to the United States from Ireland in 2007, when I was a little over two years old. My parents moved around frequently in their lives, so moving to the Bay Area was not their first time living in the United States. My family adjusted to American culture quite easily, but as I got older, the differences in my family structure became much more apparent.

The expectations that middle and high school students face in this area are vastly different to what is expected in Ireland. The majority of my family never attended any sort of higher education, and those that did made their selection mainly based on proximity to home. In Ireland, your application to a four-year university is a singular test, known as the Leaving Cert. The better you score, the wider your selection of universities and majors. Grades, harder classes, extracurriculars and whatever other achievements we cram onto our American college applications mean nothing.

Throughout my time in school, my job has been understanding the tangled mess that is American college admissions. I learned what a SAT was, when I needed to take it, where to study and what a “good” score was. I figured out what an AP test was and why I needed to take these classes. It took me reading the three-inch thick books that detailed every college in existence, writing endless lists of criteria and schools to finally understand.

I have spent a good portion of my teenage years listening to peers complain about college counselors and weekly practice SAT tests and NASA internships and who knows what else their parents forced into their lives. I have never felt that I was missing out on anything; on the contrary, having the freedom to make this process purely my own is a point of pride, and I have always been grateful to be free of the notorious expectations of Palo Altan parents. There have been difficult parts, sure. There are many past decisions that I would kill to be able to go back on. But in the end, I got it all done. No one else was going to do it for me, so I made it happen myself.

I was raised in the mindset that if I want something to be done, I have to do it myself, and my brother, for perhaps a multitude of reasons, attacks tasks in a different way. Looming deadlines provide his motivation, and his inability to research for himself has quickly led to my family requesting my help with all things relating to school. I don’t mind creating schedules and helping with homework, but the difference in how much help and advice my brother is receiving from me and our family is not lost on me. I know I organized my own life because no one in my family knew how to help me, and that makes me feel pride more than resentment. It hasn’t always been fair or easy, but being the eldest daughter of an immigrant family has given me an independence and work ethic that I am appreciative of.

Evelyn Zhang

My parents immigrated to the United States from China, my mom from Beijing and my dad from Changshu. Both of them arrived in the United States to fulfill the “American dream.” They carried the burdens of their past and their aspirations for their future in the hopes of providing their children with more opportunities than they had.

Although I feel like my identity is composed of bits and pieces of other people’s identities and what I’ve learned from others, I think my dad has contributed to shaping my identity the most. As someone who grew up extremely poor but was able to attend Tsinghua University, the top university in China, he greatly emphasizes diligence, patience and confidence. Studying hard obviously contributed to his success, but he also talks about how essential confidence is to take risks and how equally important patience is for those risks to pay off. He teaches me to be polite but assertive; to never give in but still be empathetic. The values that he’s instilled in me have significantly impacted my identity, work ethic and personality.

However, because my parents were still able to immigrate here despite the countless struggles they both went through, such as my mom’s family being persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, I feel like I have a duty to repay my parents, to make sure their sacrifice to immigrate to America was worth it. This mindset has pushed me to become a diligent and studious person so that I can get a job and earn a good living to be able to provide for my parents in the future. As the firstborn, I feel the burden, or rather the responsibility, of supporting my parents when they’re older more than my younger brother does, because of the Confucian values I grew up with. This particular value is built upon the expectation that the eldest child has the duty of taking care of their aging parents as a sign of respect, love, and duty.

Chinese culture also places a large emphasis on the success and importance of their first child, which is another component of my parents’ upbringings that’s found its place in my upbringing. Although I’m only 3 years older than my brother, I sometimes have to assume the “adult” role to fulfill this responsibility towards my parents. Though this has made me more independent, it has also put more pressure on me to make my parents proud. It also makes me feel like I have less people to confide in. I sometimes feel suffocated; since I’m expected to act like an adult, I feel like I can’t discuss some matters with my parents. However, my brother can always confide in me and I’m glad he has someone to look up to and to guide him through life.

Growing up as the eldest immigrant daughter gifted me with traits that I truly treasure about myself and had a profound impact on my identity. Despite the burdens it has also come with, I’m proud of the person that I’ve become.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”20″ display=”basic_slideshow”]Photos by Olivia Hau and Kellyn Scheel

Print Issue

Please click on the three vertical dots on the top right-hand corner, then select “Two page view.”

2021-2022 - Staff Writer

2022-2023 - Business Manager

I joined C mag because art has always been a big part of my life. I always loved looking through...

2019-2020 - Staff Writer

2020-2021 - Social Media Manager

2021-2022 - Managing Editor

Hi! I am Eunice Cho, and I am a senior at Palo Alto High...

2020-2021 - Staff Writer

2021-2022 - Online-Editor-In-Chief

I joined C Magazine because I love journalism and design. My favorite part about this...

2021-2022 - Staff Writer

2022-2023 - Editor-In-Chief

I joined C mag because I saw it as a really cool way to learn more about the Paly community,...